Helicobacter pylori seroprevalence in coronary artery disease

Mirjana Grozdovska-Naumoska

[*]

[1]

Vlatko Kotevski

[2]

Sonja Trojacanec-Piponska

[1]

Introduction

Although highly controversial when first reported (1), Helicobacter (H.) pylori infection of gastric mucosa is widely recognized today as the leading cause of chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer disease (2), as well as a common causative agent of dermatitis and gastric lymphoma and carcinoma (3). There is, however, growing evidence that chronic local infection of gastric mucosa may have systemic inflammatory effects that are responsible for atherosclerosis progression in general, and coronary artery disease (CAD) in particular (4). In addition, DNA from several infective agents has been isolated from carotid atherosclerotic plaques (5), which may mean that plaque composition makes for a particularly suitable nesting ground for these agents. Furthermore, classic inflammatory markers, such as fibrinogen and C-reactive protein (CRP), may also be directly involved in plaque maturation and rupture (6), and systemic inflammation as a result of H. pylori infection may additionally lead to endothelial dysfunction (7). There have also been reports that H. pylori infection may have a direct effect on blood pressure, although the significance of this effect remains controversial (8). In the light of all the above mentioned findings, the aim of this study was to determine the seroprevalence of H. pylori infection in a control group compared to a group of patients with coronary artery disease in order to investigate the association of H. pylori infection and CAD.

Materials and methods

The study included 102 patients (59 male and 43 female) aged 45 to 70, with chest pain and electrocardiographic evidence of CAD (ST-segment elevation). The control group consisted of 98 apparently healthy subjects, blood donors (61 male and 37 female) aged 40 to 60, with no findings indicative of CAD on clinical examination and routine biochemical tests in the reference ranges. Inclusion criteria for the patient group were: age 45 to 75 years; chest pain and ST-segment elevation upon admission; and blood sample obtained at clinic visit for routine tests. For the control group, inclusion criteria were: age 40 to 60 years; apparently healthy blood donors, with no irregular findings on clinical examination and routine biochemistry; and no evidence of CAD at the time of recruitment/blood collection. Exclusion criteria for patients were: age under 45 or over 75 years; evidence of cardiac disease other than CAD; and recent history of infectious diseases. Exclusion criteria for controls were: age under 40 or over 60 years; any evidence of overt disease; and history of using drugs such as proton pump inhibitors, H2-blockers or antibiotics. Data on socioeconomic status were collected from all study participants at recruitment.

Blood samples were taken from all subjects into vacutainers without anticoagulant, and separated serum was stored frozen at -20 ºC until analysis. The titer of IgG antibodies against H. pylori was determined with the automated EIA method from Roche Diagnostics (F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland) on a Cobas Core II immunoanalyzer. Patients with a titer of anti-H. pylori IgG antibodies above 6.6 U/mL were considered seropositive.

Statistical processing of the results was performed with the SAS Institute StatView software (version 5.0), using Fisher’s exact test to calculate χ2 and p values. A P value lower than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

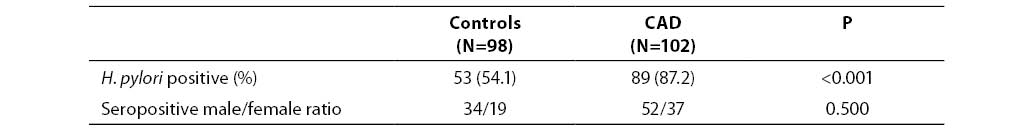

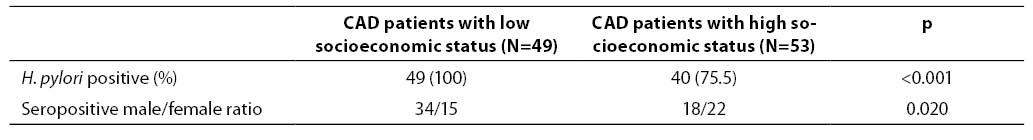

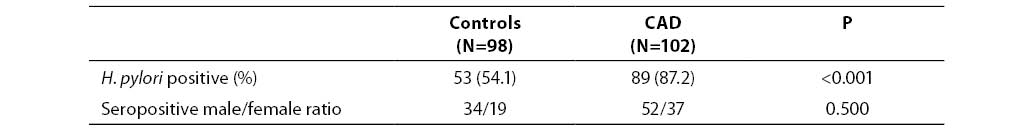

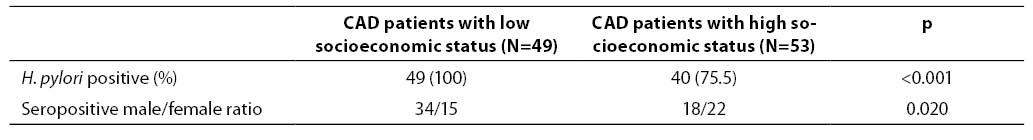

Out of 98 control subjects, 53 (54.1%) tested positive for anti-H. pylori IgG (titer >6.6 U/mL), i.e. 34 of 61 (55.7%) male subjects and 19 of 37 (51.3%) female subjects; there was no significant difference between the two subgroups. Out of 102 patients with CAD, 89 (87.2%) were positive for anti-H. pylori IgG, i.e. 52 of 59 (88.1%) male patients and 37 of 43 (86.0%) female patients. The number of seropositive individuals differed significantly between the control group and patient group (P<0.001). In addition, seropositivity was detected in the entire subgroup of patients with low socioeconomic status (N=49; 100%). The number of seropositive patients in this group differed significantly from the respective figure in patients with higher socioeconomic status (75.5% of seropositive subjects) (P<0.001). These results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Helicobacter pylori seropositivity in CAD patients and controls

Table 2. Helicobacter pylori seropositivity in CAD patients according to socioeconomic status

Discussion

The role of classic risk factors for atherosclerosis, i.e. hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes and smoking, has been well established. Today, there are increased research efforts in elucidating the role of alternative risk factors, such as cytokines, infection and immunity. There is abundant body of data concerning the possible pathogenetic mechanisms involved, most of which have been concentrated on the role of the inflammatory response mediators such as fibrinogen and CRP, and more recently interleukins (IL) such as IL-1 and IL-10, and osteopontin (9). In this regard, the association of chronic H. pylori infection and CAD is still under investigation. There have been reports that H. pylori heat shock protein 60 (Hsp60) is sufficiently similar to endothelial Hsp, so that chronic infection with H. pylori may lead to an autoimmune antibody response to endothelial cells (10). Several studies have also found increased leukocyte counts and lower HDL-cholesterol in patients infected with H. pylori (11). Irrespective of the mechanisms involved, our data provide further evidence on the link between H. pylori infection and CAD, especially in patients with electrophysiological signs of cardiac ischemia (12). There still are several methodological limitations that may confound research in the field (13).

The present study was quite modest in design and therefore suffering from some limitations that we hope to overcome in the future. One limitation was the small number of study participants, whereby the control group was not matched for sex, age and CAD risk factors. Furthermore, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes and smoking were not evaluated and correlated to H. pyloriseropositivity. Another limitation of the study was that it did not provide any evidence on the role of virulent (so called CagA+) H. pylori strains (14). Despite all this, we believe that this study may stimulate further research into the link between H. pyloriseropositivity and CAD, as our data suggest that there may be an increased seroepidemiological association of H. pylori infection with CAD.

References

1. Warren JR, Marshall BM. Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet 1983;1:1273-5.

2. Graham DY, Malaty HM, Evans DG, Evans DJ, Klein PD, Adam E. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in an asymptomatic population in United States. Effect of age, race and socioeconomic status. Gastroenterology 1991;100:1495-501.

3. El-Omar EM, Carrington M, Chow WH, McColl KE, Bream JH, Young HA et al. Interleukin-1 polymorphisms associated with increased risk of gastric cancer. Nature 2001;412(6842):99.

4. Mendall MA, Goggin PM, Molineaux N, Levy J, Toosy T, Strachan D et al. Relation of Helicobacter pylori infection and coronary heart disease. Br Heart J 1994;71:437-9.

5. Latsios G, Saetta A, Michalopoulos NV, Agapitos E, Patsouris E. Detection of cytomegalovirus, Helicobacter pylori and Chlamydia pneumoniae DNA in carotid atherosclerotic plaques by the polymerase chain reaction. Acta Cardiol 2004;59(6):652-7.

6. Patel P, Carrington D, Strachan DP, Leatham E, Goggin P, Northfield TC et al. Fibrinogen: a link between chronic infection and coronary heart disease. Lancet 1995;343:1634-35.

7. Oshima T, Ozono R, Yano Y, Oishi Y, Teragawa H, Higashi Y et al. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in healthy male subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005 19;45(8):1219-22.

8. Harvey R, Lane A, Murray L, Harvey I, Nair P, Donovan J. Effect of Helicobacter pylori infection on blood pressure: a community based cross sectional study. BMJ 2001;323:264-5.

9. Ohsuzu F. The roles of cytokines, inflammation and immunity in vascular diseases. J Atheroscler Thromb 2004;11(6):313-21.

10. Lenzi C, Palazzuoli A, Giordano N, Alegente G, Gonnelli C, Campagna MS et al. H. pylori infection and systemic antibodies to CagA and heat shock protein 60 in patients with coronary heart disease. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12(48):7815-20.

11. Kinoshita Y. Lifestyle-related diseases and Helicobacter pylori infection. Intern Med 2007;46(2):105-6.

12. Eskandarian R, Malek M, Mousavi SH, Babaei M. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with cardiac syndrome X. Singapore Med J 2006;47(8):704-6.

13. Nieto FJ. Infective agents and cardiovascular disease. Semin Vasc Med 2002;2(4):401-15.

14. Pasceri V, Patti G, Cammarota G, Pristipino C, Richichi G, Di Sciascio G. Virulent strains of Helicobacter pylori and vascular diseases: a meta-analysis. Am Heart J 2006 Jun;151(6):1215-22.