Introduction

The 76 amminoacid N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) has been proposed as a marker for evaluating and monitoring cardiac abnormalities characterized by myocardial wall stress (1). Strenuous exercise may generate transitory ischemia, myocardial stress, and diastolic left ventricular dysfunction, resulting in increased production of NT-proBNP suggestive of incipient heart disease.

Increased NT-proBNP levels after physical exercise in endurance athletes (2,3) and after heavy physical exercise in professional athletes has been described (4,5). In appropriately trained athletes, the production of this peptide is lower at rest and exercise-induced increases remain below abnormal limits (6,7). NT-proBNP concentrations in rugby players, for example, were not substantially affected by post-training recovery (passive, active recovery followed by cold-water immersion, cold-water immersion followed by active recovery) (6).

The rationale for the use of NT-proBNP, instead of mature BNP, as marker for cardiac dysfunction resides in their different half-life (90-120 versus 18 min) (8). The finding that NT-proBNP, but not intact BNP is augmented after endurance sport performance (9) is a consequence of the different life spans of the molecules.

Exercise-induced production of NT-proBNP needs to be distinguished from abnormal increases due to heart damage. NT-proBNP is a reliable diagnostic and prognostic marker in patients with suspected heart failure. Chronic elevations, along with those of other natriuretic peptides, aid in identifying and monitoring cardiac dysfunction. Differently, exercise-induced NT-proBNP changes, particularly in well-trained professional athletes, reflect an acute response to altered hemodynamics, regional wall-motion abnormalities, and exercise-induced transitory myocardial wall ischemia (10). Furthermore, exercise-induced NT-proBNP production in such athletes very likely stems from a cytoprotective mechanism (2,11).

The mechanism underlying its release has not been elucidated. Systemic inflammation following strenuous exercise may stimulate the release of NT-proBNP into the circulation (11).

Cardiac damage was inferred from high NT-proBNP concentrations measured in 60 non-professional athletes after a marathon (7): 60% of the recreational runners had increased troponin T (TnT) and NT-proBNP levels; left ventricular size and ejection fraction were unchanged but left ventricular compliance was reduced; changes in biochemical signs of cardiac damage were more pronounced in the runners who had trained at low training workloads. The study results serve as a reminder that appropriate preparation is mandatory to protect athletes against potentially harmful elevation of cardiac biomarkers and the risk of cardiac dysfunction associated with endurance performance (7).

Troponins (T and I) are commonly used diagnostic markers for cardiac ischemia and infarction. Their relevance for sports medicine was highlighted in a recently published critical review of studies on increased troponin levels after prolonged strenuous physical activity (12). With the advent of assays with high analytical sensitivity, also known as highly sensitive troponin (Hs-Tns) tests, the negative predictive value of troponin testing has improved, but its clinical specificity has substantially decreased (13).

Evaluating Tns release after prolonged strenuous exercise poses a challenging problem for clinical chemistry. Several hypotheses have sought to explain the release of cardiac proteins, focusing mainly on increased membrane permeability and leakage of the unbound cytosolic pool, which comprises only a small part of the total pool of cardiac Tns (14). Tns loss due to higher membrane permeability and the formation of “blebs” (15), i.e., membrane evaginations possibly providing the pathway for protein release, could explain the co-existence of serum Tns in a disease state and in the absence of myocardial dysfunction (16). Transient ischemia, which may occur during exercise, would not normally be sufficient to induce irreversible membrane injury: the blebs are reabsorbed or released into the circulation, where low and short-lasting amounts of Tns detectable with the new highly sensitive assays can be measured. In permanent damage, due to lack of reoxygenation, the blebs collapse and are not shed into circulation; subsequently, high amounts of Tns are released, with myocell necrosis and lysis, a feature typical of myocardial infarction.

Numerous studies utilizing last-generation Tns assays have been performed on athletes: runners (21 studies); triathletes (one study); and basketball players (one study) (12). Only one study involved 91 non-professional cyclists participating in a cycle-touring event (206 km) (17); in 43% of the cyclists, TnI exceeded the upper reference limit (URL) already at 20 min post-exercise.

Biomarkers for cardiac overload and damage have been studied in single, one-day, and ultraendurance events. A study published in 1996 and involving endurance athletes in a prolonged stage race used a now outmoded TnT assay which was affected by interference from skeletal muscle proteins. However, cardiac TnT (cTnT) was found in the serum of only 5 athletes, repeatedly in some cases, but always below the cut-off values for myocardial ischemia. On the basis of the behaviour of creatine kinase isoenzyme MB and, above all, of cTnT, it was concluded that heavy-endurance exercise repeated daily for 22 days was unable to induce permanent heart damage by acute myocardial injury in top athletes (18).

The study of biochemical parameters of cardiac damage is crucial for defining their behaviour after endurance, strenuous and continuous exercise and to avoid misinterpreting elevated serum levels. Equally important is setting cut-off values in endurance athletes to avert misrecognition of signs of myocardial overload or frank pathology.

Evaluating cardiac response is essential for improving our understanding of the physiology of endurance. Here we report on the changes in NT-proBNP and Hs-TnT in relation to energy expenditure in professional athletes during a 3-week staged cycling race, a universally accepted model of strenuous exercise.

Materials and methods

Subjects

This prospective, non-comparative interventional study involved 9 professional cyclists from the Liquigas-Cannondale professional cycling team. All subjects had participated in the 2011 Giro d’Italia and were followed during the duration of the race from 8 through 29 May 2011.

The mean completion time for the cyclists was 86:47:29 h (range, 84:12:10-88:15:51 h) with a mean speed of 35.7 km/h. The median age was 26 years (range, 24–33). Height, weight and body-mass index (BMI) were measured the morning before the start of each stage under fasting and rest conditions (Table 1). Diet was strictly controlled by team physicians.

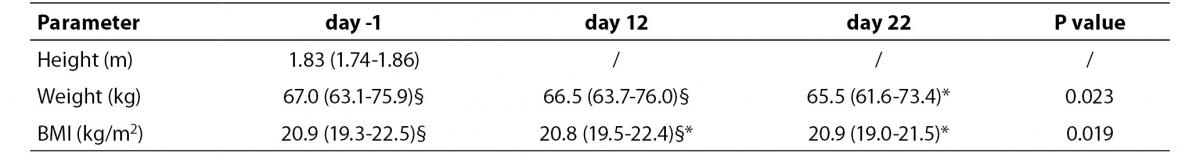

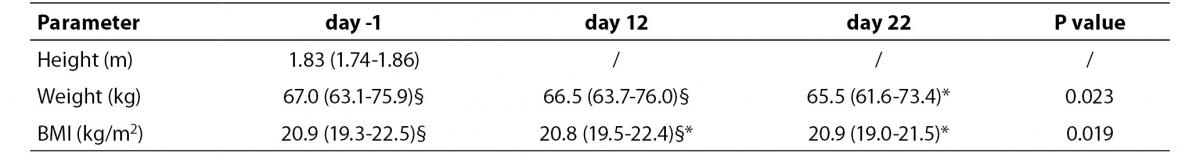

Table 1. Anthropometrical measurements recorded at the three time-points. Measurements are expressed as median and distribution range (5th – 95th percentile). The different superscripts denote statistical significance at P < 0.05.

Three subjects received non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and antibiotics for an upper respiratory tract infection for 5 days during the first week (one case) and during the second week (two cases).The 2011 Giro d’Italia was a “no-needle” race in which therapies and drugs were permitted only for evident illness.

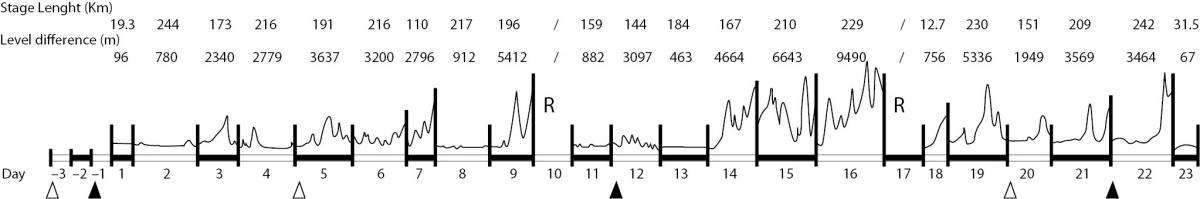

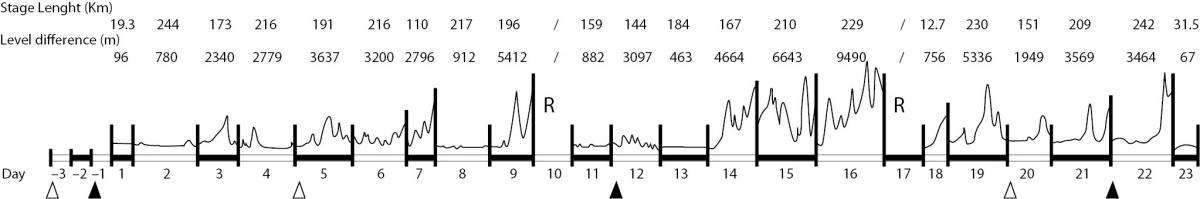

Blood drawings were performed on the day before the start (day -1), on the 12th day (day 12), and on the final day of the race (day 22) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Race features. The diagram illustrates length (km) and difference in elevation (m) of each stage, day of each stage, days of rest (R), day of blood sampling for this study (), and day of blood sampling for official anti-doping testing (∆).

The total net energy expenditure (kcal) for each stage was derived from the developed power measured with a power sensor (PowerMeter™, SRM GmbH, Jülich, Germany) incorporated into the bike pedal (sensitivity ± 2%). The measures taken during the race are relative to the day before the blood drawings to allow the determination of correlation.

The study design and protocol were approved by the reference ethical committee (ASL Città di Milano); informed consent was obtained from all subjects before the beginning of the study.

Methods

Blood drawings

Adherence to pre-analytical recommendations was strictly observed to prevent factors from inadvertently affecting the analytical data. The Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) and World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) rules for collection and transport of specimens were followed (19,20).

Blood drawing was performed between 08.00 hrs and 10.00 hrs after overnight fasting with subjects resting in bed for 10 minutes after awaking.

Evacuated tubes (BD Vacutainer Systems, Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) were used for the haematological tests (BD K2EDTA 3.5 mL tubes); 7 mL plain tubes (BD SSTII Advance) were used for clinical chemistry tests. Immediately after blood drawing, the tubes were inverted 10 times and stored in a sealed box at 4 °C. Controlled temperature was assured during transport: a specific tag (Libero Ti1, Elpro, Buchs, Switzerland) was used for temperature measurement and recording. The samples were transported by car or train and car: the time elapsed between blood drawing and arrival at the laboratory was 1.30 hrs on day -1, 7.50 hrs on day 12, and 1.30 hrs on day 22. After arrival at laboratory, the K2EDTA-anticoagulated blood was homogenized for a minimum of 15 min with an appropriate mixer prior to analysis, as recommended by the UCI Blood Analytical Protocol (January 2009) and the Athlete Biological Passport Operating Guidelines WADA (January 2010) (19,20). Plain tubes were immediately centrifuged 1300 x g at 4 °C for 10 min and the serum was stored at -80 °C until analysis.

Cardiac indexes

Resting heart rate and diastolic and systolic pressure were measured in the morning with the subjects resting in bed immediately after awakening. The measurements were performed in duplicate at the wrist with an OMRON R3™ (Omron Healthcare Co. Ltd, Kyoto, Japan).

Calculation of plasma volume changes

Repeated measurement of blood parameters in humans during and after physical activity is influenced by changes in plasma volume (21). The percentage variation in plasma volume (DPV%) at consecutive time-points was calculated according to the formula (21):

DPV%= 100 x [(Hbpre / Hbpost) x (1-Htpos t/ 100)/

(1-Htpre / 100)] - 100;

where Hbpre and Hbpost are the pre- and the post-intervention haemoglobin (Hb) concentration, respectively, and Htpre and Htpost are the pre- and the post-intervention haematocrit (Ht) percentages, respectively.

The analyte concentrations measured at days 12 and 22 were corrected for relative changes in PV% using the following equation:

Corrected values = uncorrected values x

[100-DPV(%)] / 100

Measurement of cardiac biomarkers

NT-proBNP and Hs-TnT levels were measured on a Roche Modular Analytics EVO analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Lewes, Sussex, UK) with Elecsys® proBNP and Elecsys® Hs-TnT, respectively. Both methods are based on sandwich immunodetection.

Serum NT-proBNP measurement had an analytical range of 5-35,000 ng/L, an inter-assay coefficient of variation (CV) of 0.7 to 1.6%, and an intra-assay CV of 5.3 to 6.6%. Serum Hs-TnT measurement had aninter-assay CV of 8% at 10 ng/L and 2.5% at 100ng/L, and an intra-assay CV of 5% at 10 ng/L and 1% at 100 ng/L.The analytical range of this assay is 2 to 10,000 ng/L.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism® ver. 5.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). All values in the descriptive analysis are expressed as median and distribution range (5th-95th percentile). Friedeman’s test was used to compare values over time with Dunn’s post-hoc test. The widening in TnT amplitude distribution was evaluated by the Levene’s test. Correlation analysis between the measured parameters was performed using the two-tailed Spearman’s rank correlation test. Significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Anthropometrical measurements

There was a significant decrease in both body weight and BMI during the race. At day 22, weight significantly differed from that measured at day -1 and day 12, while BMI was significantly lower than at day -1 (Table 1).

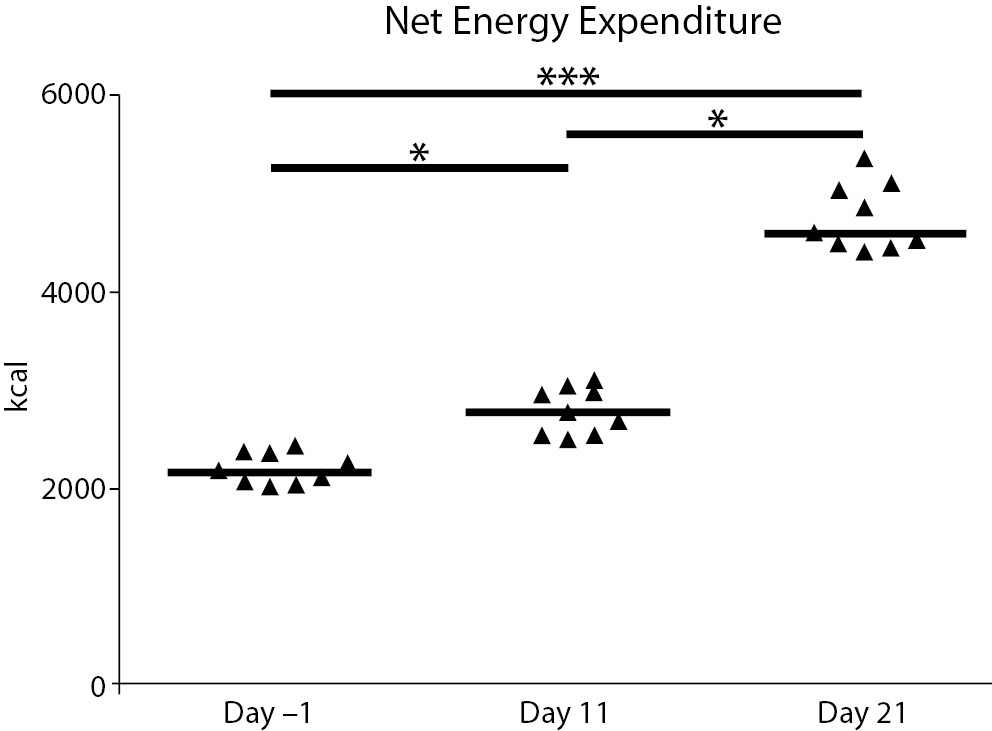

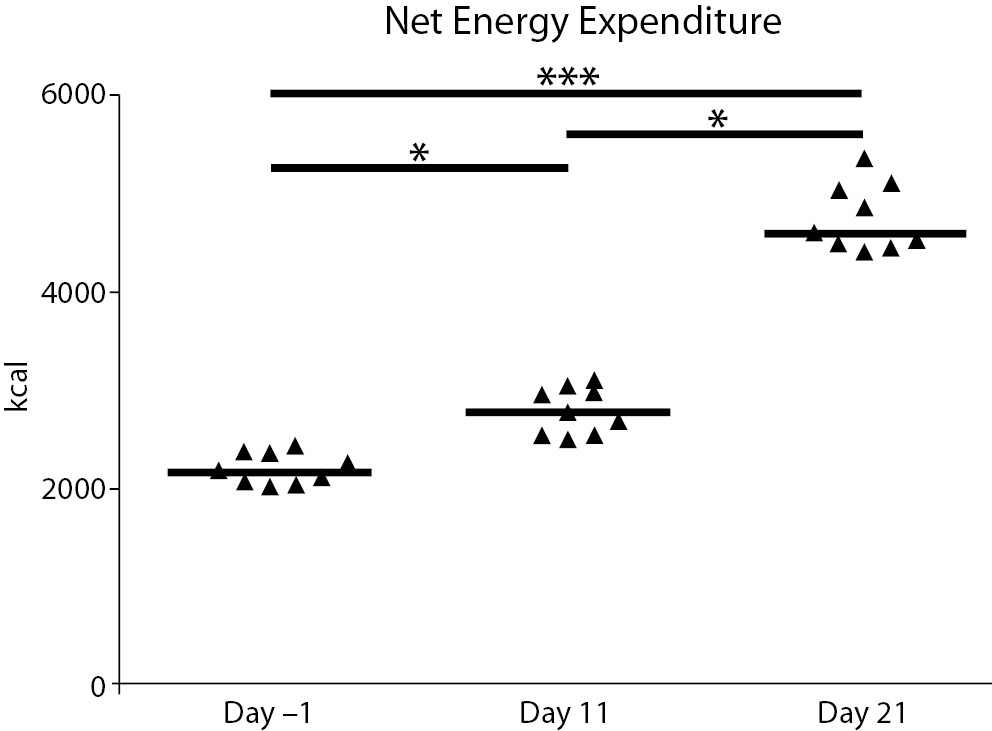

Except for the baseline values, the energy expenditure was calculated for the days before the blood drawings to evaluate a possible relationship between the previous metabolic effort and the consequent physiological response.

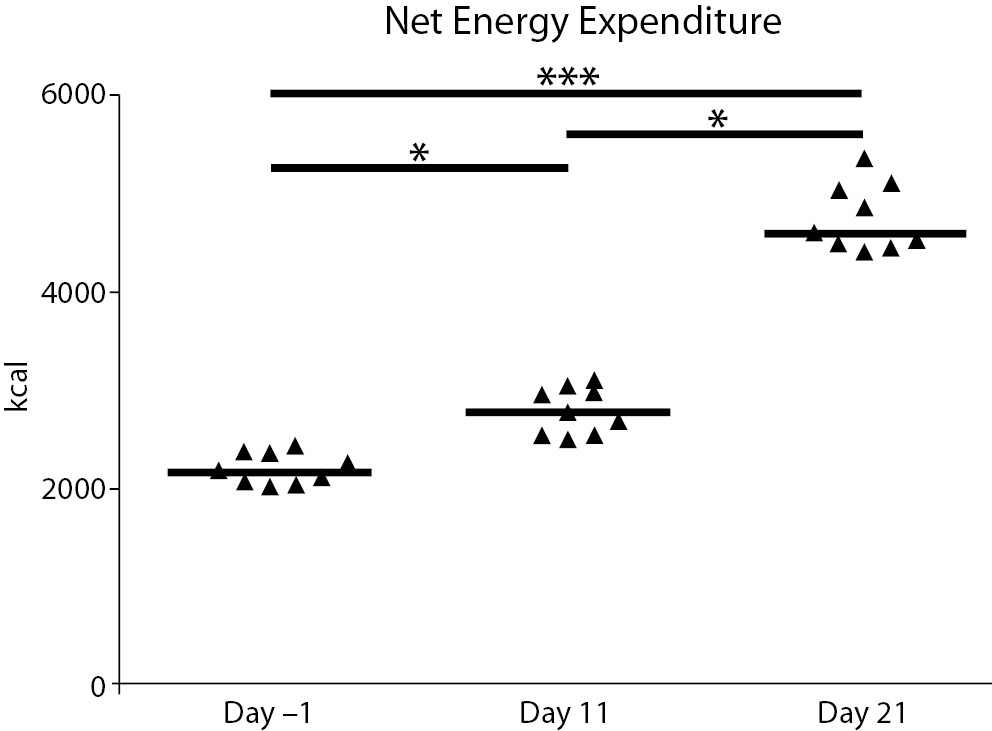

A significant difference in net energy expenditure between the three time-points was seen. Energy expenditure increased by about 21% between the rest values and day 12 (P = 0.039), 39% between days 12 and 22 (P = 0.008), and 52% between days -1 and 22 (P < 0.001) (Figure 2). The increase observed at day 21 was related to the differences in topographic elevation during the second half of the race: the first part of the race was composed of 5 plain stages, 3 middle-high mountain stages, and 2 high-mountain stages (total difference in elevation 21,952 m); the second part was composed of 3 plain stages, 3 middle-high mountain stages, and 5 high-mountain stages (total difference in elevation 40,313 m) (Figure 1).

Figure 2. Net energy expenditure during the race. The graph shows the total net energy expenditure at baseline (day -1) and the days before the following blood drawings (day 11 and day 21). Triangles denote the individual concentrations of the analytes; the solid lines denote the median; *P < 0.05, ***: P < 0.0001

Cardiac indexes

Resting heart rate and systolic and diastolic blood pressure values remained unchanged during the race.

Changes in plasma volume

As calculated with the Dill & Costill formula (21), no significant changes in plasma volume were observed during the race. Descriptively, the median PV% increased in the first part of the race (day -1 to day 12) by 1.55% (0.45-3.34) and decreased in the second part by -0.72% (-1.95-0.80) (day 12 to day 22). The net increase in PV between days -1 and 22 was 0.99% (-0.86-2.34).

The changes in PV paralleled those in both [Hb] and Ht, which did show significant variations during the race. [Hb] decreased from day -1 [146 g/L (137-154)] to day 12 [131 g/L (127-142)] (P = 0.031) but did not significantly increase between days 12 and 22 [133 g/L (127-150)]; the net variation over baseline to the end of the race was significant (P = 0.004).

The same trend was observed for Ht: a decrease from day -1 [42.7% (40.8-44.8)] to day 12 [39.2% (37.8-42.1); P = 0.009], followed by an insignificant increase from day 12 to day 22 [39.8% (37.8-44.0)]; the net variation over baseline to the end of the race was significant (P = 0.010).

Biomarker analysis

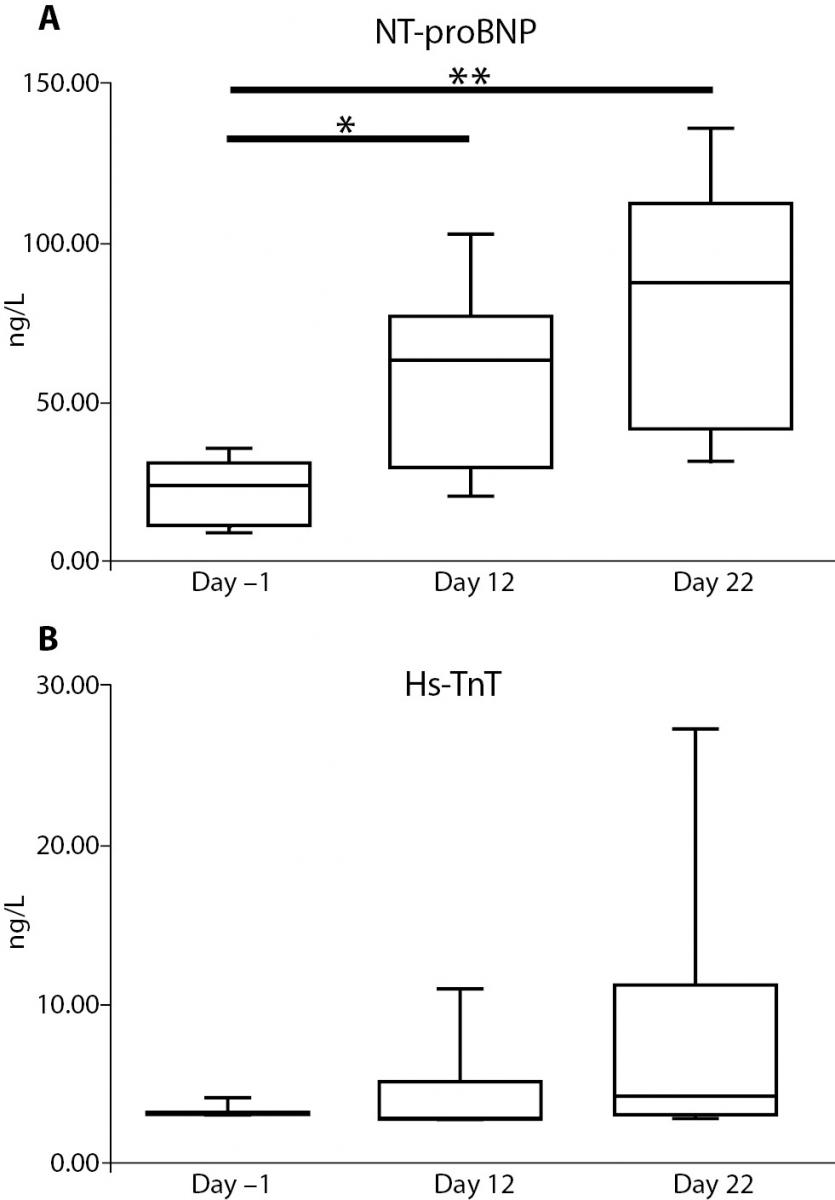

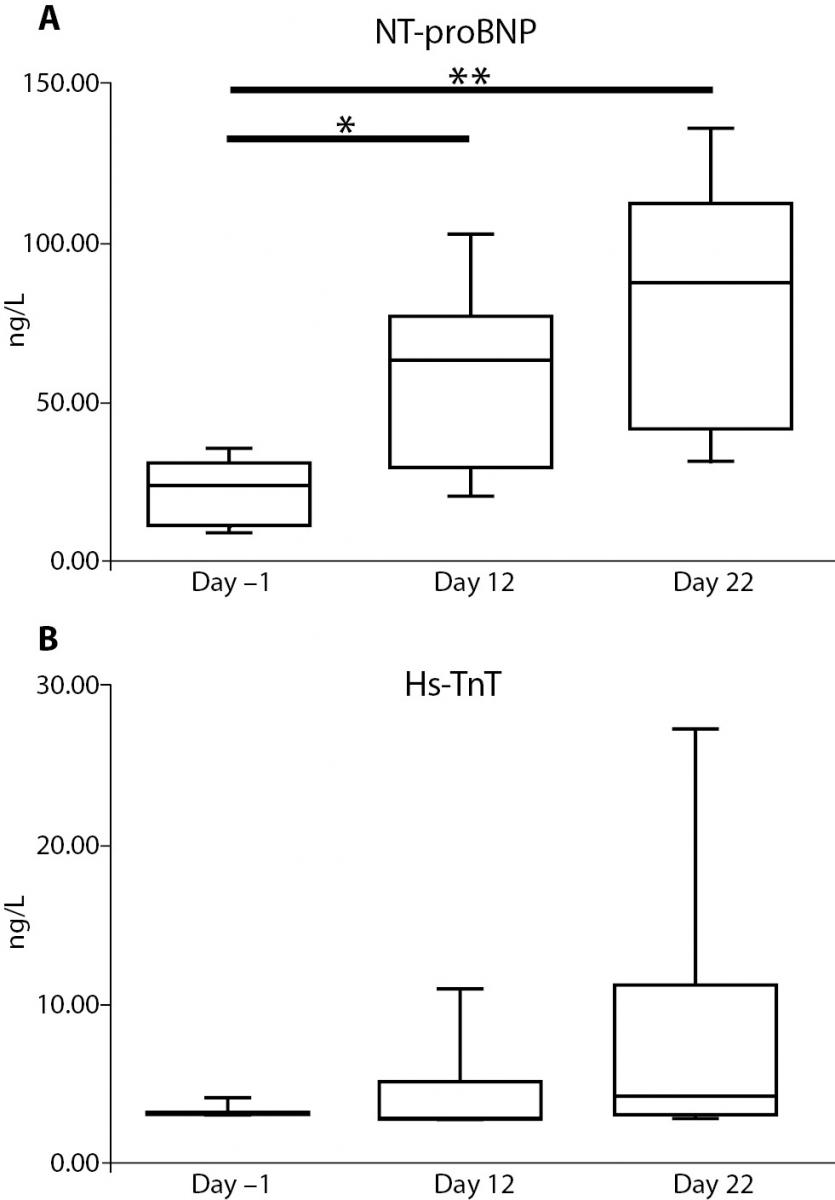

Serum NT-proBNP increased significantly over baseline from 23.52 ng/L (9.67-34.33) at day –1 to 63.46 ng/L (22.15-93.31) at day 12 (P = 0.039) and to 89.26 ng/L (34.66-129.78) at day 22 (P < 0.001).

No differences were found in serum Hs-TnT levels: 3.00 ng/L (3.00-3.88) ng/L at day -1; 3.34 ng/L (3.00-9.33) ng/L at day 12; and 4.26 ng/L (3.00-21.90) ng/L at day 22. However, there was a significant widening in the amplitude distribution of the values from day -1 to day 22 (P < 0.001). Figure 3 reports the trend for the cardiac biomarker concentrations.

Figure 3. Changes in serum cardiac markers during the race. The graph shows the trend for concentrations of NT-proBNP (panel A) and Hs-TnT (panel B). *: P < 0.05, **: P < 0.001.

A fairly positive correlation was found between NT-proBNP and Hs-TnT levels (r = 0.44, P = 0.022).

When NT-proBNP concentrations were corrected for DPV% changes, the significance was kept but their levels were found to increase: day -1 vs. day 12 (P < 0.001); day -1 vs. day 22 (P < 0.001) and day 12 vs. day 22 (P = 0.008). The PV% change did not affect the TnT concentrations.

A moderately significant negative correlation was also found between BMI and NT-proBNP concentration (r = -0.54, P = 0.004) but not between BMI and TnT concentration (r = -0.25, P = 0.199).

No correlations were found between either biomarker concentration and PV%; however, while there was a fairly significantly correlation between the percentage variation in NT-proBNP concentration and the DPV% across the time-points (r = 0.47, P = 0.015), no such correlation was seen for TnT concentration (r = -0.08, P = 0.694).

There was a significant and moderately negative correlation between NT-proBNP and heart rate (r = -0.51, P = 0.006) but not between heart rate and TnT (r = -0.19, P = 0.348).

NT-proBNP concentrations fairly correlated with systolic pressure (r = 0.39, P = 0.046) but not with diastolic pressure (r = 0.32, P = 0.081).

Interestingly, there was a significant correlation between NT-proBNP and net energy expenditure (r = 0.70, P < 0.001) and a fairly significant correlation with TnT (r = 0.39, P = 0.013).

Discussion

NT-proBNP levels increased significantly during the 3-weeks stage race and were accompanied by a widening of the standard deviation, with high inter-individual variability, particularly after heavy and strenuous endurance exercise in these athletes, as observed previously (3,7,22). Increased NT-proBNP may be interpreted as a possible sign of transitory heart damage and a potential risk for both professional and recreational athletes alike (23). Reports of abnormally high post-race NT-proBNP concentrations (182 ng/L) in non-professional marathoners highlight the potentially dangerous effects of endurance performance on the heart. However, the starting median one study found in non-professional athletes was already high (106 ng/L), inevitably affecting interpretation of the data (7). Resting NT-proBNP values in marathoners (28.8 and 44 ng/L) (5, 22), mountain marathoners (39.7 ng/L) (4) and the pre-race values in our cyclists were within the reference limits for the general population (24). These cyclists were well-trained professional athletes capable of withstanding high, specific workloads; therefore, despite continuous stimulation of heart wall, the stable, low values could be considered a typical feature of their physiological condition.

Our data are in line with those obtained in 20 endurance athletes (10 triathletes, 5 cyclists, 5 marathoners) (median concentration of 24.7 ng/L versus 28.9 ng/L in the controls) (2). Low NT-proBNP concentrations were also found in 50 professional cyclists (mean of 23.6 ng/L versus36.3 ng/L in 35 sedentary subjects) (10).

Strenuous physical exercise increases the production of NT-proBNP in professional athletes. The end-race values we found were similar to those reported after a mountain marathon (median of 97.6 ng/L) (9) and a marathon (150.2 ng/L) (3). Such increases could result from the repeated release of NT-proBNP which, because of continuous and stressful exercise, is not completely recovered. Following a bout of 3-hour long exercise in trained subjects, NT-proBNP increased from 19 to 49 ng/L and then fell to 38 ng/L within 3 hours after the end of the exercise (2). In the present study, the release of NT-proBNP may have been constant during the race: gradual recovery was possible during the easier first part but was hindered by the much more difficult second part (differences in elevation of 21,952 m versus 40,313 m). This is confirmed by the strong correlation between the trends for NT-proBNP concentration and energy expenditure as a measure of physical effort.

No data exist about NT-proBNP behaviour in professional cyclists. One study involving 29 recreational cyclists during the 2004 Ötztal Radmarathon evaluated NT-pro-BNP. NT-proBNP significantly increased from 28 ± 21 to 278 ± 152 ng/L immediately after the race, and then decreased the following day before returning to baseline values 1 week later (25). Differences between professional and non-professional athletes aside, the dramatic increase in the biomarker in these recreational athletes is evident. Because of its typical release kinetics, the authors attributed the decrease in NT-pro-BNP to an adequate volume regulatory response of a hemodynamically stressed heart to prolonged strenuous exercise.

A bimodal increase in NT-proBNP was reported in 10 trained male cyclists (age, 40.0 ± 4.5 years) who simulated the 2007 Tour de France. After the third stage of the race simulation, NT-proBNP increased up to 200 ng/L, returned to 50 ng/L at stage 12, before increasing again to about 250 ng/L at stage 17 (26). It should be remarked that the rise in NT-proBNP was linked to impaired diastolic function causing residual diastolic ventricular filling. Systolic function, represented primarily by global and segmental ejection fractions, was not affected until about stage 9, after which the values stabilized or rose slightly. A direct connection with cardiac biomarkers was not observed (26). In our sample of professional cyclists, although cardiac function did not change during the race, a mild but significant correlation was found between NT-proBNP and both heart rate (negatively) and systolic pressure (positively).

Increased NT-proBNP during and after exercise is linked to the growth-regulating properties of BNP, which regulates myocardial adaptation in healthy athletes (2) and is physiologically induced by systemic inflammatory cytokines (11) rather than being a clear and undoubted sign of heart damage, which rarely occurs (27).

Troponin release after exercise, especially after endurance events, has been reported mostly in runners and marathoners. Exercise-induced cTnT release was apparent in almost half of endurance athletes according to a meta-analysis of 26 relevant studies (1120 cases) (28).

The interpretation of elevated Tns is undefined. Current guidelines for the identification of acute myocardial infarction are based on positive serum troponin values. However, a number of studies have reported positive values for cTnT levels in asymptomatic, healthy subjects after endurance exercise, suggesting that positive cTnT values can result after strenuous exercise (29). The introduction in laboratory routine of highly sensitive assays for cTnT has increased the possibility of their misclassification: while these tests have higher analytical sensitivity (i.e., low limit of detection) and a higher negative predictive value of troponin, their clinical specificity is lower (12). The reference population where the 99th percentile limit of the reference value distribution (99th URL) obtained with assays having a coefficient of variation < 10% at those levels must be accurately selected for obtaining clinically valid data (30).

There are few studies on Hs-TnT levels in athletes. After a marathon, Hs-TnT was higher than the URL (0.016 μg/L) in 86% of 70 male and 15 female amateur runners (age range, 45-49 years) (31). In another study on 10 male amateur marathoners with a similar age range, Hs-TnT was higher than the URL (0.012 μg/L) after an ultramarathon of 216 km, but unexpectedly, the percentage of positivity immediately after the race was lower than that described after a classical marathon (40%) (32).

A similar positive percentage after a classical marathon was, however, reported in amateur male runners by using the lowest URL (0.010 μg/L; 43%) (33). After a marathon, Hs-TnT kinetics revealed a peak immediately after the race that decreased rapidly to pre-test values within 72 h (median, 31.07 μg/L and 3.61 μg/L, respectively) in 102 healthy men (mean age, 42 ± 9 years). The authors stated that kinetics with a sharp peak indicate that cardiac necrosis during marathon running, though seemingly very unlikely, are a function of altered myocyte metabolism (34).

Data on professional cyclists during prolonged performances or by using Hs-cTnT are lacking. One study using a second-generation cTnI assay on trained male cyclists who simulated the 2007 Tour de France found a 30% increase in cTnI after the first stage. The positive value percentage decreased until stage 12, when 50% of the sample showed positive values, and then peaked at stage 15 (60%), before the positive values returned to 30% at stages 17 and 18 (26). Positive values were measured in 6 out of 10 cyclists but were not homogeneously distributed over time, with some subjects showing only two positive values during the stage race, whilst others showed five or more positive values. The highest number of positive values was recorded during the stages of the third week.

While troponin release during a 3-weeks stage race does not appear to be predictable, there is a rough relationship between its release and the demand and technical difficulties of race stages. Our data confirm this finding: while only one subject had detectable, but within range, TnT concentrations at pre-race, we found only one positive value (> 0.010 μg/L) at half race and 3 out of 11 (23%) at the end of the race.

A study involving professional cyclists during a Giro d’Italia was performed using a first-generation cTnT assay. In 25 athletes from five different teams, blood drawings were performed before the race and at 7, 14, and 21 days. Participant withdrawals from the race and dropouts from the study reduced the final study population from 17 to 10 subjects. TnT was detected in 5 athletes, repeatedly in some cases, in a total of 10 samples out of 64, but without exceeding the cut-off for assuming myocardial damage (18). In general, we can assume that we observed similar results. However, the specificity of the two assays is completely different, since skeletal troponin might have interfered with the results obtained from the old assay. Moreover, a stable haematocrit was reported in that study (18), while plasma volume and consequently haemodilution was observed in ours.

The data we obtained in professional cyclists during a 3-weeks stage race hold particular interest and fill a gap in the current literature on cardiac markers during and after endurance exercise.

This is the first study to describe the behaviour of cardiac stress markers in professional cyclists during a 21-days stage race. The main finding is the evidence for an association between changes in cardiac biomarker concentrations (NT-proBNP and TnT) and net energy expenditure, and indirectly the metabolic effort spent during prolonged endurance performance.

The main limitation of our study resides in the small sample size. The number of subjects was dictated by belonging to the team, collaborating in the study, other than being derived from a sample size calculation. Moreover, NSAIDs and antibiotic therapy was administered in three cases. Even if the treatment was specific for respiratory tract infection and brief, a possible effect of NSAIDs on cardiac biomarkers cannot be ruled out. In conclusion, elevated NT-proBNP during a 3-weeks cycling stage race could be interpreted as an adaptation of the heart in response to stimulation by a very high workload and heavy and stressful exercise, as demonstrated by the increased energy expenditure. The link between increased NT-proBNP and altered cardiac function, and the recovery of diastolic impairment described in prolonged cycling in particular, needs to be further explored.

Also, elevated troponin concentrations may result from the extreme effort involved during such an endurance sport event. Although the concentrations of both biomarkers fell within the physiological range, with only a few subjects exceeding the upper range limits, the possible event of transient overload, which must be recovered before exercise is resumed, poses a health concern in individuals with occult heart disease.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Liquigas-Cannondale pro-cycling team for their participation and assistance in logistics during the study. We wish to thank Dr Antonino Coco for performing the blood drawings at day 12. We are also indebted with Mr Kenneth Britsch for language editing and with Dr Alessandra Grotta for her help in statistical revision.

Notes

Potential conflict of interest

None declared.

References

1. Mottram PM, Haluska BA, Marwick TH. Response of B-type natriuretic peptide to exercise in hypertensive patients with suspected diastolic heart failure: correlation with cardiac function, hemodynamics, and workload. Am Heart J 2004;148:365-70.

2. Scharhag J, Urhausen A, Schneider G, Herrmann M, Schumacher K, Haschke M, et al. Reproducibility and clinical significance of exercise-induced increases in cardiac troponins and N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide in endurance athletes. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2006;13:388-97.

3. Melanson SE, Green SM, Wood MJ, Neilan TG, Lewandrowski EL. Elevation of myeloperoxidase in conjunction with cardiac-specific markers after marathon running. Am J Clin Pathol 2006;126:888-93.

4. Banfi G, Lippi G, Susta D, Barassi A, D’Eril GM, Dogliotti G, et al. NT-proBNP concentrations in mountain marathoners. J Strength Cond Res 2010;24:1369-72.

5. Lippi G, Schena F, Salvagno GL, Montagnana M, Gelati M, Tarperi C, et al. Influence of a half-marathon run on NT-proBNP and troponin T. Clin Lab 2008;54:251-4.

6. Banfi G, D’Eril GM, Barassi A, Lippi G. N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) concentrations in elite rugby players at rest and after active and passive recovery following strenuous training sessions. Clin Chem Lab Med 2008;46:247-9.

7. Neilan TG, Januzzi JL, Lee-Lewandrowski E, Ton-Nu TT, Yoerger DM, Jassal DS, et al. Myocardial injury and ventricular dysfunction related to training levels among nonelite participants in the Boston marathon. Circulation 2006;114:2325-33.

8. Mair J, Hammerer-Lercher A, Puschendorf B. The impact of cardiac natriuretic peptide determination on the diagnosis and management of heart failure. Clin Chem Lab Med 2001;39:571-88.

9. Banfi G, Migliorini S, Dolci A, Noseda M, Scapellato L, Franzini C. B-type natriuretic peptide in athletes performing an Olympic triathlon. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2005;45:529-31.

10. Lippi G, Salvagno GL, Montagnana M, Schena F, Ballestrieri F, Guidi GC. Influence of physical exercise and relationship with biochemical variables of NT-pro-brain natriuretic peptide and ischemia modified albumin. Clin Chim Acta 2006;367:175-80.

11. McLachlan C, Mossop P. Are elevations of N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide in endurance athletes after prolonged strenuous exercise due to systemic inflammatory cytokines? Am Heart J 2006;152:e1.

12. Lippi G, Cervellin G, Banfi G, Plebani M. Cardiac troponins and physical exercise. It’s time to make a point. Biochem Med 2011;21:55-62.

13. Plebani M, Zaninotto M. Cardiac troponins: what we knew, what we know - where are we now? Clin Chem Lab Med 2009;47:1165-6.

14. Giannoni A, Giovannini S, Clerico A. Measurement of circulating concentrations of cardiac troponin I and T in healthy subjects: a tool for monitoring myocardial tissue renewal? Clin Chem Lab Med 2009;47:1167-77.

15. Hickman PE, Potter JM, Aroney C, Koerbin G, Southcott E, Wu AH, et al. Cardiac troponin may be released by ischemia alone, without necrosis. Clin Chim Acta 2010;411:318-23.

16. Lippi G, Banfi G. Exercise-related increase of cardiac troponin release in sports: An apparent paradox finally elucidated? Clin Chim Acta 2010;411:610-1.

17. Serrano-Ostariz E, Legaz-Arrese A, Terreros-Blanco JL, Lopez-Ramon M, Cremades-Arroyos D, Carranza-Garcia LE, et al. Cardiac biomarkers and exercise duration and intensity during a cycle-touring event. Clin J Sport Med 2009;19:293-9.

18. Bonetti A, Tirelli F, Albertini R, Monica C, Monica M, Tredici G. Serum cardiac troponin T after repeated endurance exercise events. Int J Sports Med 1996;17:259-62.

21. Dill DB, Costill DL. Calculation of percentage changes in volumes of blood, plasma, and red cells in dehydration. J Appl Physiol 1974;37:247-8.

22. Herrmann M, Scharhag J, Miclea M, Urhausen A, Herrmann W, Kindermann W. Post-race kinetics of cardiac troponin T and I and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide in marathon runners. Clin Chem 2003;49:831-4.

23. Thompson PD, Apple FS, Wu A. Marathoner’s heart? Circulation 2006;114:2306-8.

24. Hess G, Runkel S, Zdunek D, Hitzler WE. Reference interval determination for N-terminal-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP): a study in blood donors. Clin Chim Acta 2005;360:187-93.

25. Neumayr G, Pfister R, Mitterbauer G, Eibl G, Hoertnagl H. Effect of competitive marathon cycling on plasma N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin T in healthy recreational cyclists. Am J Cardiol 2005;96:732-5.

26. Williams K, Gregson W, Robertson C, Datson N, Whyte G, Murrell C, et al. Alterations in left ventricular function and cardiac biomarkers as a consequence of repetitive endurance cycling. Eur J Sport Sci 2009;9:97-105.

27. Pedoe DST. Marathon cardiac deaths - The London experience. Sports Medicine 2007;37:448-50.

28. Shave R, George KP, Atkinson G, Hart E, Middleton N, Whyte G, et al. Exercise-induced cardiac troponin T release: a meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2007;39:2099-106.

29. Eijsvogels TM, Shave R, van Dijk A, Hopman MT, Thijssen DH. Exercise-induced cardiac troponin release: real-life clinical confusion. Curr Med Chem 2011;18:3457-61.

30. Collinson PO, Heung YM, Gaze D, Boa F, Senior R, Christenson R, et al. Influence of population selection on the 99th percentile reference value for cardiac troponin assays. Clin Chem 2012;58:219-25.

31. Mingels A, Jacobs L, Michielsen E, Swaanenburg J, Wodzig W, van Dieijen-Visser M. Reference population and marathon runner sera assessed by highly sensitive cardiac troponin T and commercial cardiac troponin T and I assays. Clin Chem 2009;55:101-8.

32. Giannitsis E, Roth HJ, Leithauser RM, Scherhag J, Beneke R, Katus HA. New highly sensitivity assay used to measure cardiac troponin T concentration changes during a continuous 216-km marathon. Clin Chem 2009;55:590-2.

33. Knebel F, Schimke I, Schroeckh S, Peters H, Eddicks S, Schattke S, et al. Myocardial function in older male amateur marathon runners: assessment by tissue Doppler echocardiography, speckle tracking, and cardiac biomarkers. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2009;22:803-9.

34. Scherr J, Braun S, Schuster T, Hartmann C, Moehlenkamp S, Wolfarth B, et al. 72-h kinetics of high-sensitive troponin T and inflammatory markers after marathon. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43:1819-27.