Introduction

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) occurs in the western world with a frequency of approximately 1 per 1000 individuals per year (1). The clinical conditions that predispose DVT are: increasing age, cancer, prolonged immobilization, stroke, previous DVT, congestive heart failure, hormonal treatment, pregnancy or puerperium, acute inflammatory bowel disease, atherosclerotic disease, long air travel (2,3). However, DVT also occurs without an obvious precipitating factor. As DVT is a condition with significant morbidity, rapid diagnosis and effective anticoagulant treatment is required (4,5).

The test of choice for clinically suspected DVT is compression ultrasonography (CUS) (6). The sensitivity for proximal DVT has been reported as 97% but for calf DVT it could be considerably less (73%) (7). Repeated or serial venous ultrasound examination is indicated for initially negative examination result in symptomatic patients, DVT ‘unlikely’ patients (by Wells score), and patient with negative D-dimer test (8). CUS procedure is time consuming and expensive. Therefore, considerable efforts are being made to design diagnostic algorithms to improve the diagnosis of DVT-suspected outpatients.

In recent years, new diagnostic methods involving assessment of clinical probability and D-dimer become proven diagnostic strategy of outpatients with suspect DVT (8). The inclusion of D-Dimer measurements as a first step in diagnostic work-up was recommended (9). Recently, a large number of rapid D-dimer assays have been developed for exclusion of DVT. They differ with respect to assay design, the monoclonal antibodies employed to capture the antigen from plasma, the type of calibrators used and the cut-off levels to exclude DVT. In addition, published reports suggest that the positive and negative predictive values of the various commercial D-dimer assays are highly variable (10).

Taking into account the clinical symptoms and signs of DVT, calculation of the pre-test clinical probability score (PTP) for DVT before D-dimer measurement and CUS utilisation could be useful (8). PTP for DVT can be calculated using modified Wells score with nine items: active cancer, paralysis or recent immobilization of the lower limbs, recently bedridden or recent major surgery, localized tenderness, leg swelling, calf swelling, edema of symptomatic leg, collateral veins, previous VTE and alternative diagnosis (8).

At best, D-dimer alone or in combination with PTP score may be used to confidently exclude DVT quickly, removing the necessity for time consuming and expensive imaging techniques.

The aims of this study were two-fold: firstly to examine the cost-effectiveness of the three different D-dimer measurements in the screening of DVT, alone or in combination with PTP, before CUS examination and secondly to compare the total costs of D-dimer assays and CUS utilisation (alone and in combination with PTP) in the screening of DVT and to identify the diagnostic alternative with minimal cost for detecting DVT.

Materials and methods

Subjects

We analyzed data of 192 (95 male and 97 female) prospectively identified outpatients with clinically suspected acute DVT admitted to the vascular ambulance at Department of Clinic for Vascular Surgery, Clinical Centre of Serbia, from January to May 2011. Patients were referred from primary care physicians or sent in from other clinics. Patients were excluded if clinical symptoms persisted for more than 7 days, if they had been hospitalised for more than 3 days at the time of inclusion into the study or had been treated with therapeutic doses of un-fractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin for more than a day or with vitamin K antagonists before attempted inclusion. Patients were not excluded if DVT had occurred previously in the other leg. All included patients were over 18 years of age.

All patients were evaluated by the vascular ultrasound specialist. The data about gender, age and data for calculation of the PTP score were collected. We used scoring system for patient classification. One point was awarded for each of the following items if present: active cancer, paralysis or recent immobilization of the lower limbs, recently bedridden or recent major surgery, localized tenderness, leg swelling, calf swelling, edema of symptomatic leg, collateral veins, previous VTE. Two points were awarded for alternative diagnosis (8). Patients with a PTP score of less than two (low + moderate PTP) were considered DVT-unlikely, while those with a score of two or more (high PTP) were considered DVT-likely (11).

DVT diagnosis was determined by venous duplex sonography including CUS and colour Doppler visualisation of the veins within the symptomatic leg. Duplex ultrasound examinations were performed by vascular ultrasound specialist according to a standardised protocol and report form (12) CUS was performed within 3 hours of outpatients admission to the vascular ambulance. Patients were classified as DVT positive if they had DVT confirmed by CUS or as DVT negative if CUS was negative.

All patients gave informed consent prior to their enrolment in the study according to the ethic guidelines following the Helsinki Declaration. The institutional review committee approved our study protocol confirming that we had followed local biomedical research regulations.

Methods

Peripheral venous blood was drawn into collection tubes (Vacutainer, Becton Dickinson, USA) containing sodium citrate as anticoagulant (0.105 mol/L). Blood sampling was performed within 2 hours of outpatients admission to the vascular ambulance. Plasma was obtained by centrifugation at 2000 x g for 10 min and stored in aliquots at -70 °C. D-dimer was determined using three different assays. Vidas D-dimer Exclusion II (BioMérieux, Marcy L’Etoile, France) is quantitative automated ELISA with fluorescent detection determined on Mini Vidas Immunoanalyser (BioMerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). Hemosil D-dimer HS (Instrumentation Laboratory, Milan, Italy) is automated quantitative latex-based immuno-agglutination assay determined on Elite Pro (Instrumentation Laboratory, Milan, Italy). Innovance D-dimer (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Products GmbH, Germany) is particle-enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay determined on BCS (Dade-Behring Coagulation System). All three D-dimer tests were performed on all 192 patients.

Statistical analysis

For both decision-analytic models (DAMs) we set the cut-off value at which the negative predictive value (NPV) for D-dimer was at least 95%. For the first DAM we calculated the cut-off value for D-dimer in the total patients group and for the second DAM we calculated the PTP-specific cut-off value in the DVT-unlikely group (13). D-dimer cut-off values for the first DAM were 0.65 mg/L fibrinogen equivalent units (FEU), 268 ng/mL and 0.60 mg/L FEU for Vidas D-dimer Exclusion II, Hemosil D-dimer HS and Innovance D-dimer, respectively. D-dimer cut-off values for the second DAM were 0.68 mg/L FEU, 268 ng/mL and 0.65 mg/L FEU for Vidas D-dimer Exclusion II, Hemosil D-dimer HS and Innovance D-dimer, respectively. The Newcomb-Wilson hybrid confidence intervals (CI) score was calculated for the number needed to screen (NNS). This improved, narrower CI, provides rational estimates when sample size is small (14,15).

All calculations were performed using Microsoft Excel, EduStat 2.01 (2005, Alpha Omnia, Belgrade, Serbia) and MedCalc for Windows version Version 9.6.3. (Mariakerke, Belgium). The minimal statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. For cost-effectiveness analysis TreeAge module Healthcare version 1.5.2 was used (TreeAge Software INC., Williamstown, USA).

Outcome, ICER, CMA and sensitivity analysis

The perspective of the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) analysis is the clinical laboratory setting. To estimate effectiveness we calculated the number needed to screen (NNS) to find one true positive patient selected for CUS. The NNS is analogous to “number needed to treat” and it was calculated as the reciprocal value of the difference between the prevalence of true positive patients (TPP) and prevalence of false negative patients (FNP). The corresponding formula is:

NNS = 1 / [ (prevalence of TPP) – (prevalence of FNP)] (16).

The meaning of NNS could be interpreted as the number of patients that should be sent to CUS to find one DVT positive patient. In other words, the smaller the NNS the more accurate is the D-dimer test for DVT diagnosis. NNS depends on cut-off values for a particular D-dimer assay.

For ICER analysis we also calculated the NNS% (100/NNS), a value with a clearer clinical understanding. The meaning of NNS% could be interpreted as the percentage of patients that should be sent to CUS to find one from 100 DVT positive patients.

For each DAM we performed ICER analysis by ranking the three alternatives by their increasing costs. After eliminating alternatives that were more or equally costly and less effective than a competing alternative (ie; ruled out by simple dominance), the ICER of each alternative was calculated as the additional cost of that alternative divided by its additional effectiveness, compared with the next most costly alternative (17).

Another point of interest was the cost from the perspective of a third-party payer - Republic Institute for Health Insurance (RIHI), the leading health care provider, responsible for health care of almost the entire Serbian population (7.5 million). Outcome of interest was DVT diagnosis. If outcomes are known to be equal, only costs are analysed and the least costly alternative is chosen (17). We calculated all direct costs required to diagnose DVT per patient:

direct cost = direct cost per D-dimer tests + (number of patients selected for CUS × direct cost per CUS examination).

In this cost minimisation analysis (CMA), we compared direct costs for all six strategies (three strategies from the first DAM and three strategies from the second DAM).

However, we applied the sensitivity analyses. Sensitivity analyses were conducted for factors that could possibly restrict the generalisability of the study results. This approach systematically varies the critical parameters of variables to determine whether the overall decision criteria changes (18). In our analysis critical variables are costs and effectiveness; we varied them within specific intervals and recalculated results in order to see the magnitude of change on the final estimate. Two-way sensitivity analysis was performed by simultaneously varying the total costs and effectiveness within the given intervals (19). NNS were varied within the 95% CI and cost according to the number of daily outpatients to the vascular ambulance. To the vascular ambulance the average number of daily outpatients is 3. The base costs used were the average costs per patient using the service when 3 patients are admitted to vascular ambulance per day. However, for sensitivity analyses we used costs for minimal number of outpatients at the vascular ambulance (1 patient) and for 10 patients. We assumed that range of 1 to 10 patients for cost calculation included all necessary variation in costs for controls and calibrations.

Results

Costs calculation

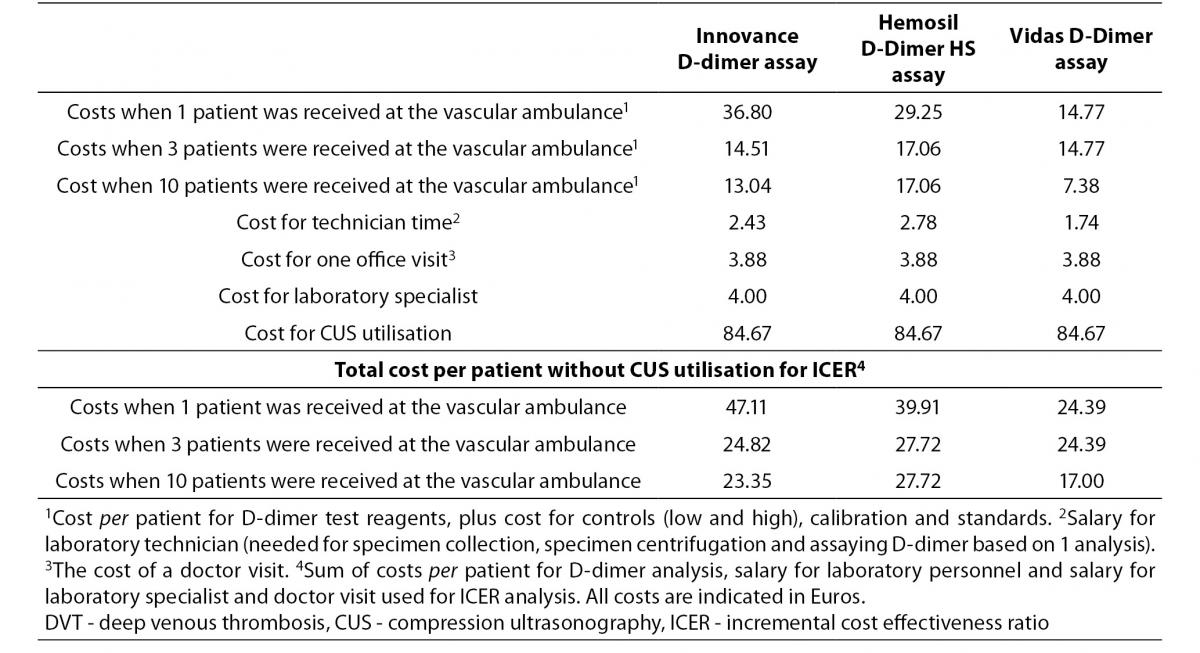

The direct cost estimations were based on the costs of diagnostic procedures and staff doctor visits. The consumed diagnostic procedures included measurements of D-dimer concentration by D-dimer assays, consumables required for operation of the automated analyser and disposables needed for specimen collection and sample analysis. Furthermore, diagnostic procedures included CUS utilisation.

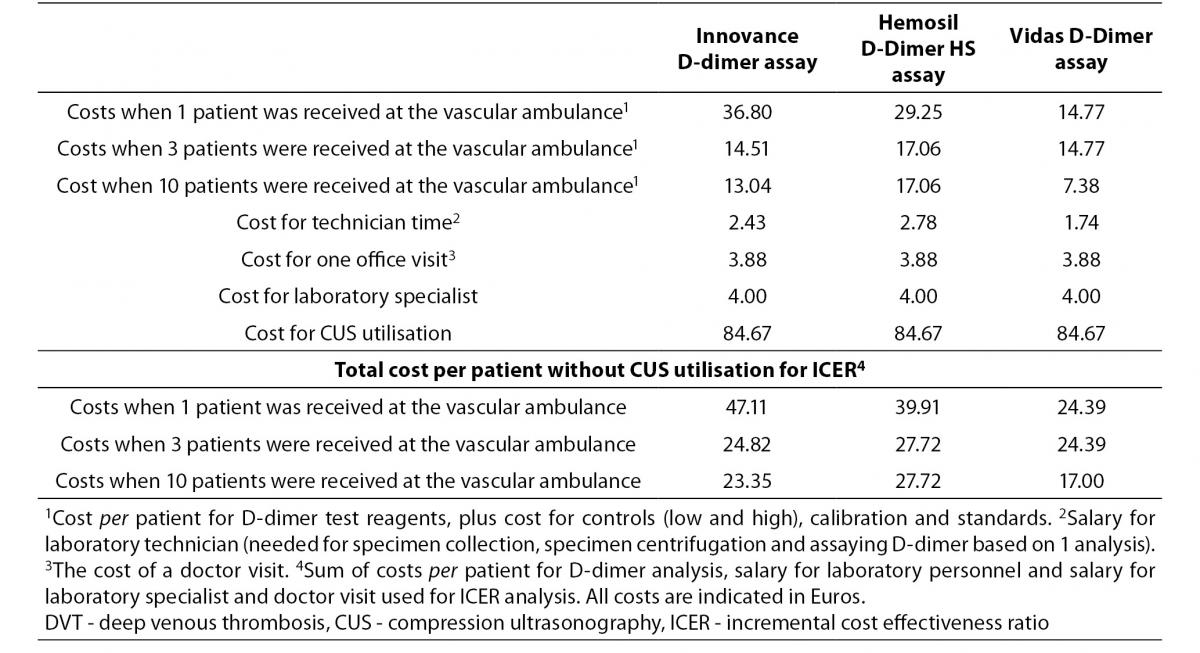

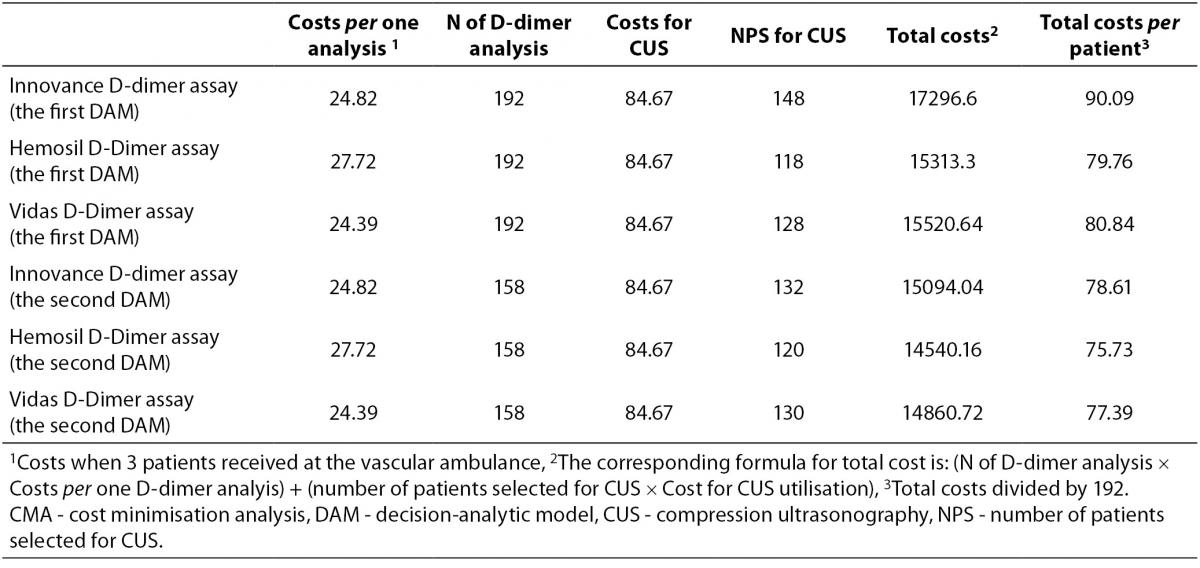

We calculated costs per patient that used the laboratory service. These costs included cost for D-dimer test reagents, for controls (low and high), calibrators and standards, all calculated per patient. The assumption for this calculation is that average number of daily admitted patients to the vascular ambulance is three (Table 1). We calculated the costs for laboratory specialists and laboratory technicians. The costs of laboratory specialists were the same for all D-dimer analyses, since evaluation of results takes approximately same amount of time. To this we added the costs for the laboratory technician’s time for specimen collection, specimen centrifugation and D-dimer measurements. Laboratory technician’s costs were different since every D-dimer assays required different time for measurement. In addition, we added the cost of a doctor visit. The costs of a doctor visit were the same since examination of patients takes approximately the same amount of time for all screening alternatives. For ICER analysis we summarised cost for D-dimer reagents, costs for the laboratory technician’s time, cost of laboratory specialist and the cost of a doctor visit. The total cost for CMA was calculated by adding the costs for CUS procedure to previously mentioned costs. The cost for vascular ultrasound specialist is included in the cost for CUS procedure.

Table 1. Total cost per patient for diagnostic resources included in DVT diagnosis.

Due to the fact that we set the cut-off values at which the NPV was at least 95% in every diagnostic alternative FNP were 2. If patients have a low D-dimer value, the D-dimer level should be re-analysed after seven days (8). Accordingly, all costs for patients with low D-dimer value were doubled.

Administrative costs (e.g. electricity) were excluded from the calculations since these costs are the same for all compared strategies. Non-health care costs and indirect costs were not included in the analysis. All costs are calculated in Euros.

In order to estimate the average cost per patient we used market prices and prices of RIHI for 2011 (20). The former refers to the average prices for laboratory tests. The latter refers to the estimated actual average prices of staff doctor visits, laboratory technicians, laboratory specialist work, disposables needed for specimen collection and CUS utilisation (Table 1).

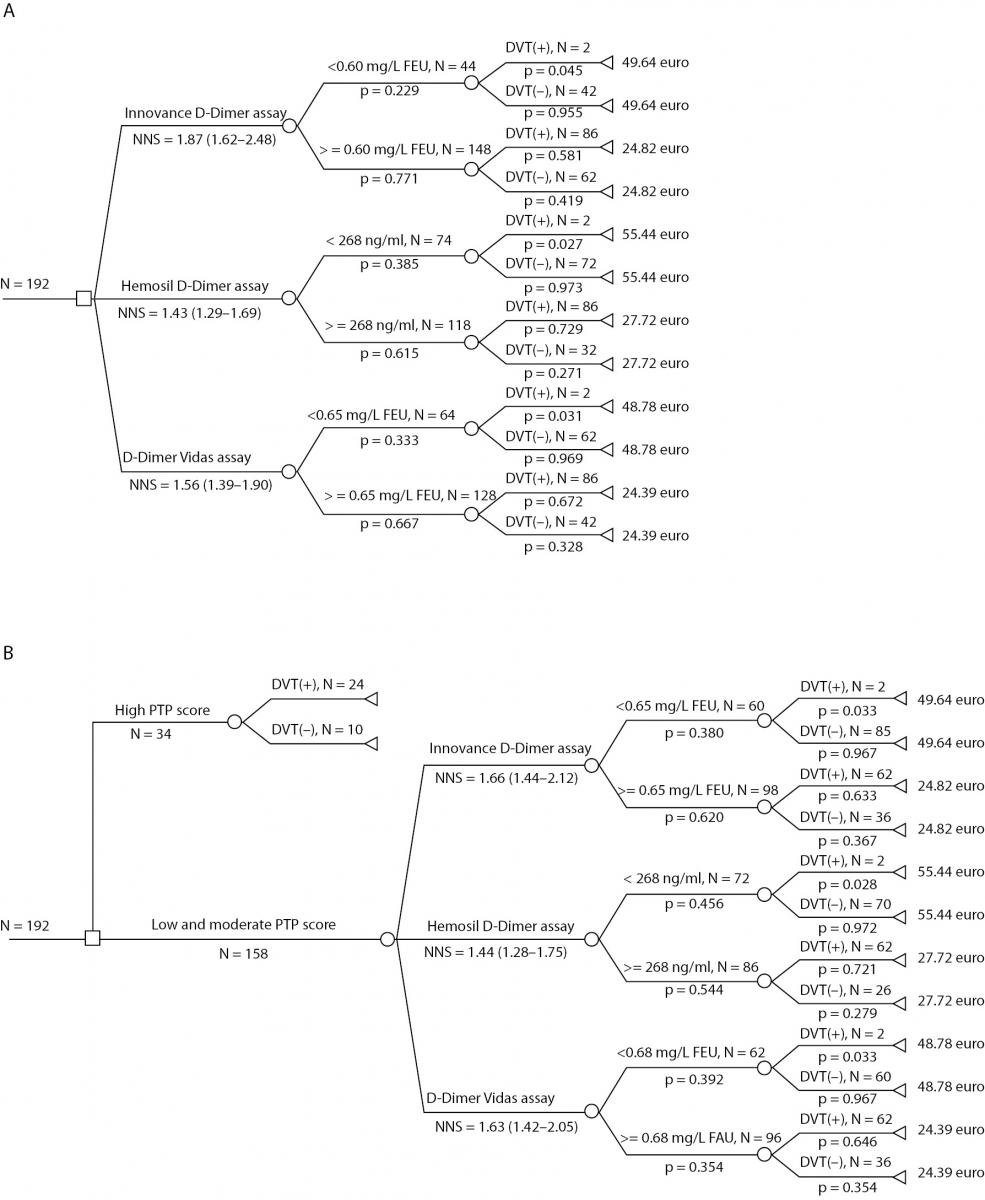

The decision-analytic models

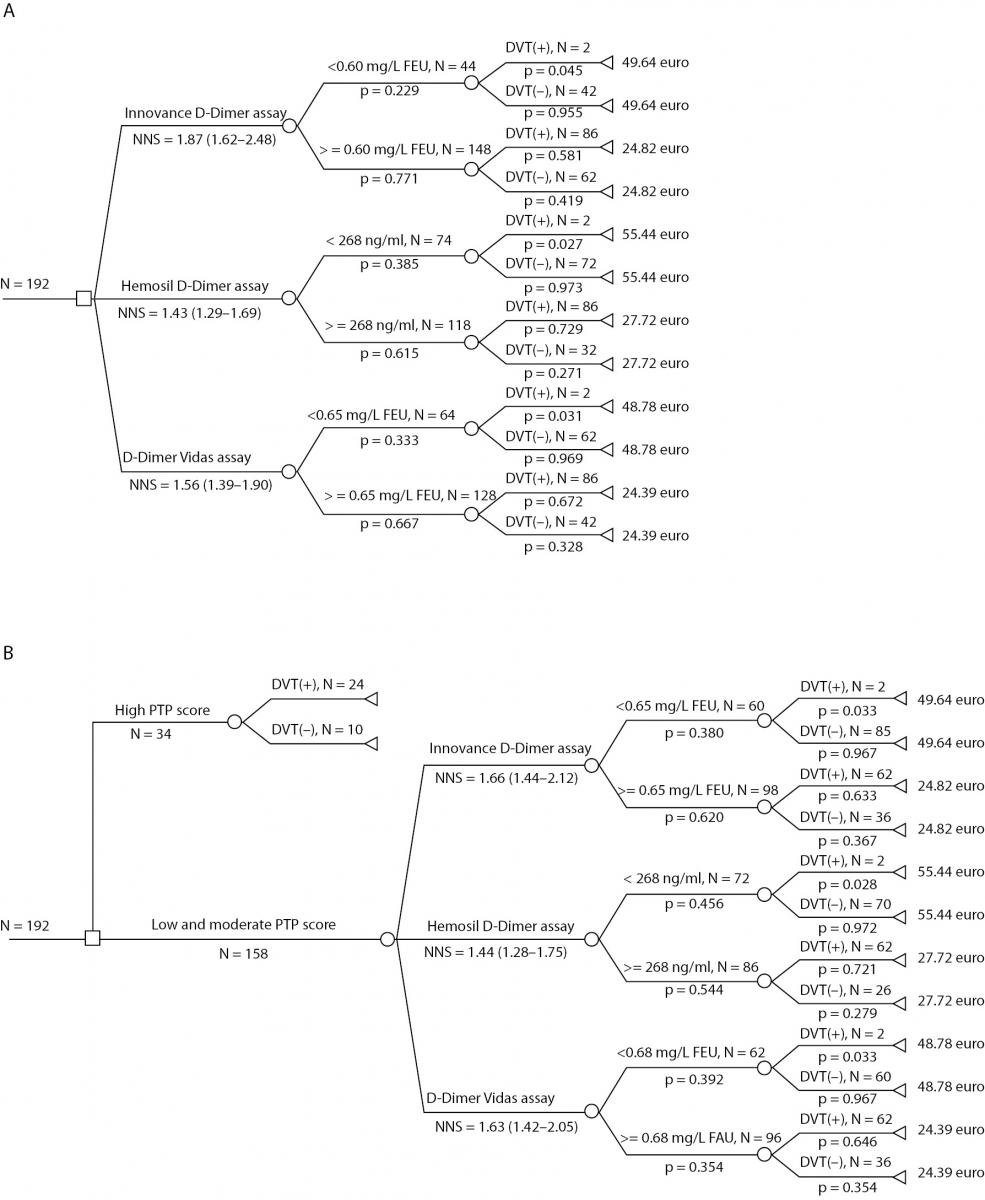

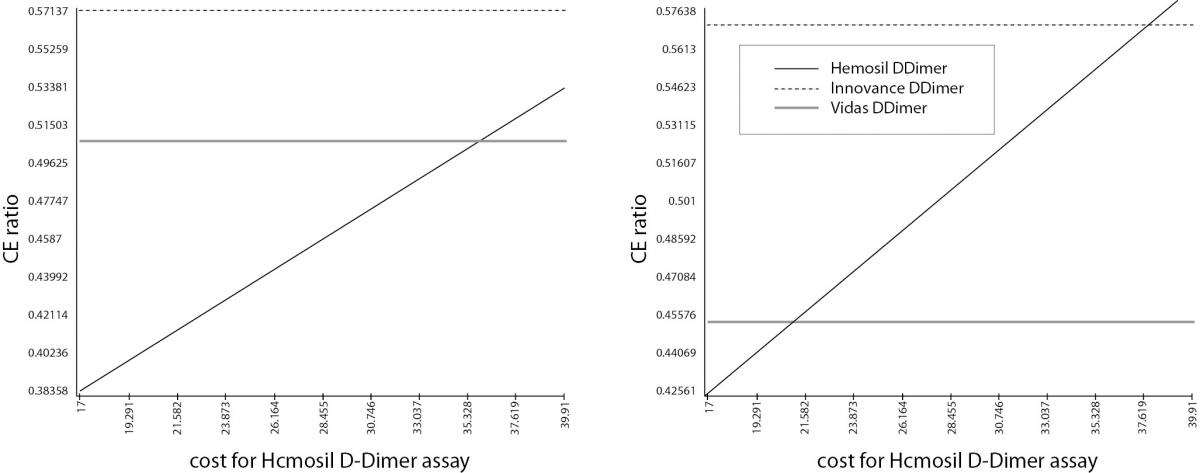

The first DAM involved all the included outpatients (the total patient group) and the selection procedure according to D-dimer measurements. Within it we estimated the number of patients selected for CUS and costs of three strategies: DVT screening with Innovance D-dimer reagents; DVT screening with D-dimer Hemosil HS reagents and DVT screening with Vidas D-dimer Exclusion II (Figure 1, Panel a). In the second DAM selection of patients was the firstly done according to PTP score. 34 outpatients had high PTP. As the prevalence of DVT patients with high PTP is 75-80% (1,5), CUS was performed without D-dimer testing only for these 34 patients (Figure 1, Panel b). The remaining 158 patients with low and moderate PTP (DVT-unlikely group) were selected for CUS according to D-dimer measurements and costs were calculated for three strategies as in the previous model.

Figure 1. DAMs for diagnosing of DVT. Panel A) The first DAM involved all the included outpatients and within it NNS and costs for three strategies: DVT screening with the Innovance D-dimer assay; DVT screening with the D-dimer Hemosil HS assay and DVT screening with the Vidas D-dimer Exclusion II assay; Panel B) The second DAM involved patients with low and moderate PTP selected from the total patients group and NNS for three strategies as in the previous model.

Costs for Innovance D-dimer assay in the first DAM were calculated: cost for every branch multiply by all probabilities for that branch eg. 49.64 Euros x 0.045 x 0.229 =0.51 Euros. The costs for all four branches were summarized.

The number needed to screen (NNS); deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pre-test probability (PTP) score, the decision-analytic model (DAM)

Base case analysis

The NNS value (1.87) was higher in the first DAM than NNS value (1.66) in the second DAM when the selection was made according to the Innovance D-dimer assay. In contrast, NNS values selected according to Hemosil D-dimer HS assay and Vidas D-dimer Exclusion II assays were higher in the first DAM (Figure 1, Panel a and Panel b).

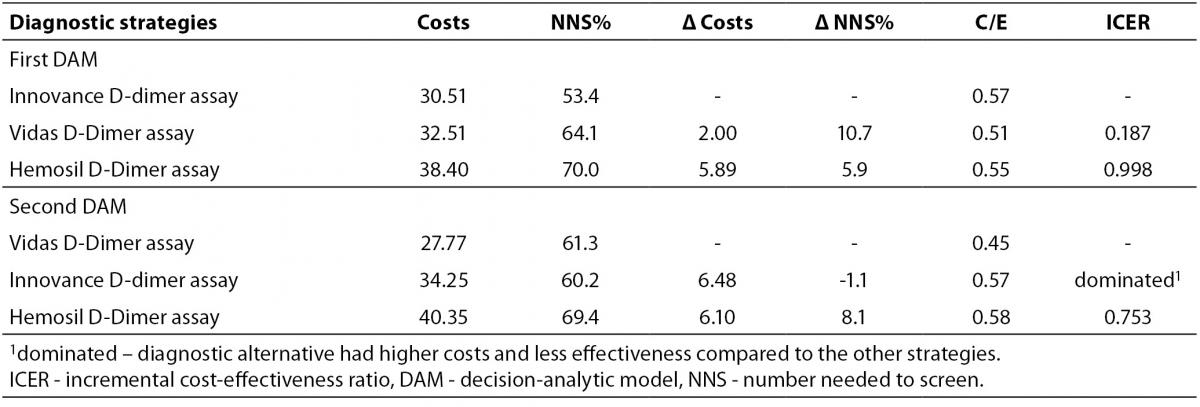

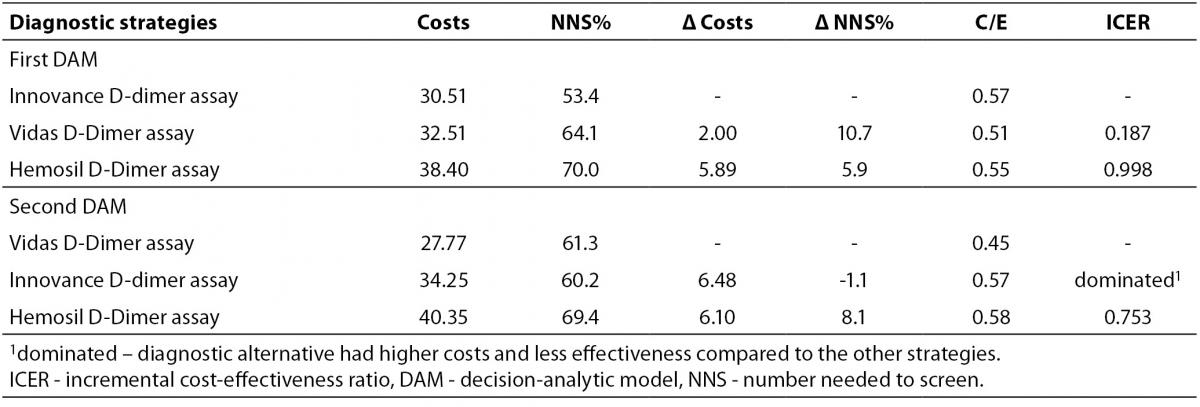

Diagnostic strategies employing different D-dimer assays were compared using ICER analysis. The results for both DAM are shown in Table 2. For the first DAM, no alternatives were clearly dominated by any other. The diagnostic alternative employing the Vidas D-dimer Exclusion II assay gave a lower ICER value (0.187 Euros per one additional DVT positive patient from 100 patients selected for CUS) than the alternative employing the Hemosil D-dimer assay (0.998 Euros per one additional DVT positive patient from 100 patients selected for CUS). However, in the second DAM, the Innovance D-dimer assay was more expensive and less effective than the D-dimer Vidas Exclusion II assay therefore it was ruled out by simple dominance. The diagnostic alternative employing the Vidas D-dimer Exclusion II assay had a lower ICER (0.450 Euros per one DVT positive patient from 100 patients selected for CUS) than the alternative employing the Hemosil D-dimer HS assay (0.753 Euros per one DVT positive patient). As a consequence the Vidas D-dimer Exclusion II assay was marked as the dominant alternative in the second DAM.

Table 2. ICER analysis of diagnostic scenarios for the first and the second DAM.

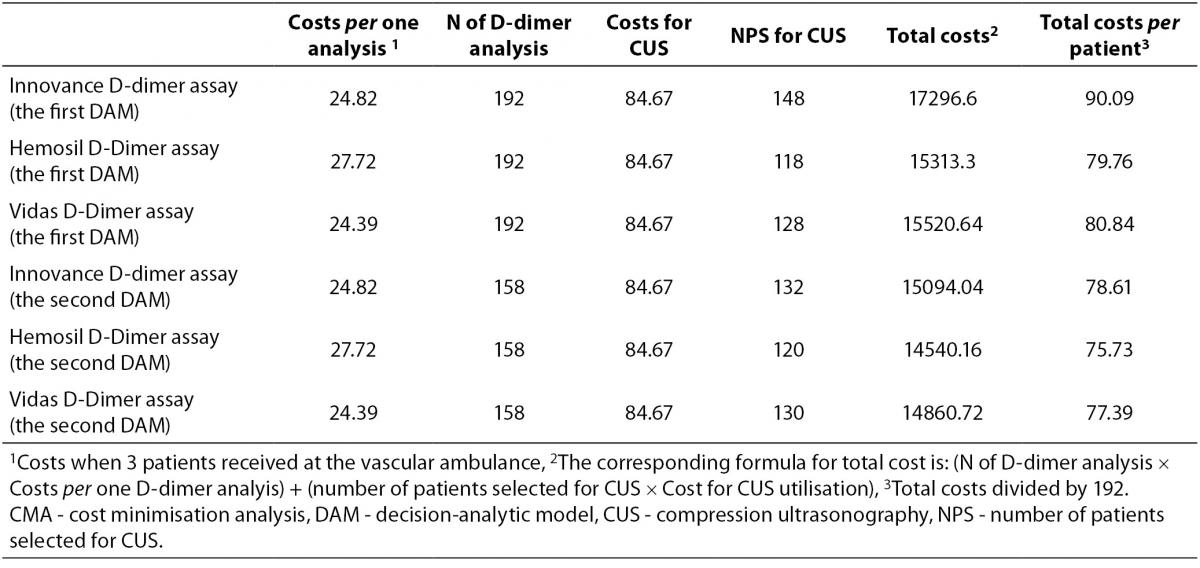

CMA results are presented in Table 3. The total average cost per patient for each diagnostic alternative, according to the number of patients selected for D-dimer testing and CUS utilisation, in DAMs with or without PTP scoring is indicated. It is clear that the selection of patients according to PTP score followed by D-dimer analysis decreases the number of patients selected for CUS examination as well as the average cost per patient for all three D-dimer assays. The diagnostic alternative employing PTP scoring followed by Hemosil D-dimer HS measurement was less costly in comparison to other strategies. Savings were up to 14.26 Euros per patient.

Table 3. CMA of diagnostic scenarios for the first and the second DAM

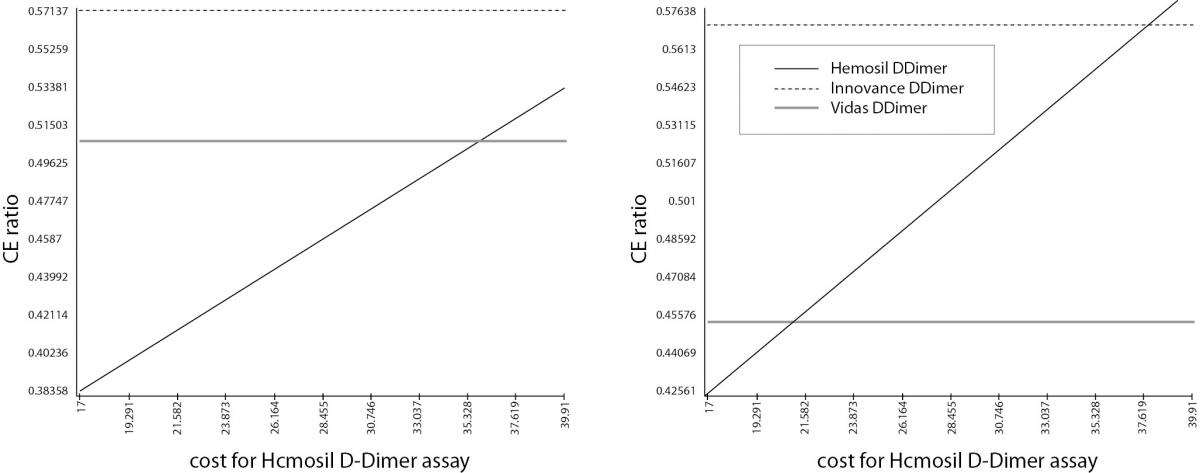

Sensitivity analysis

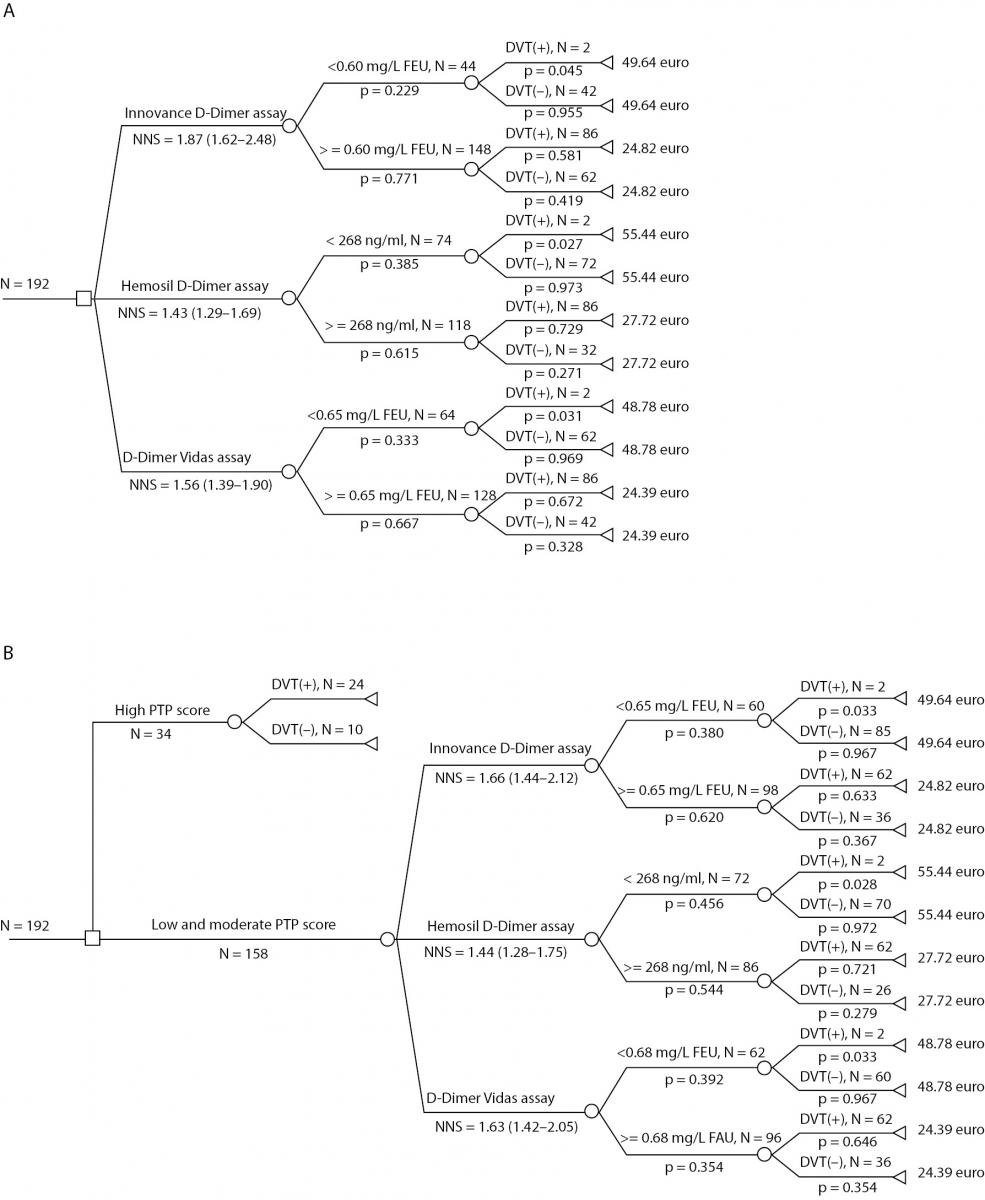

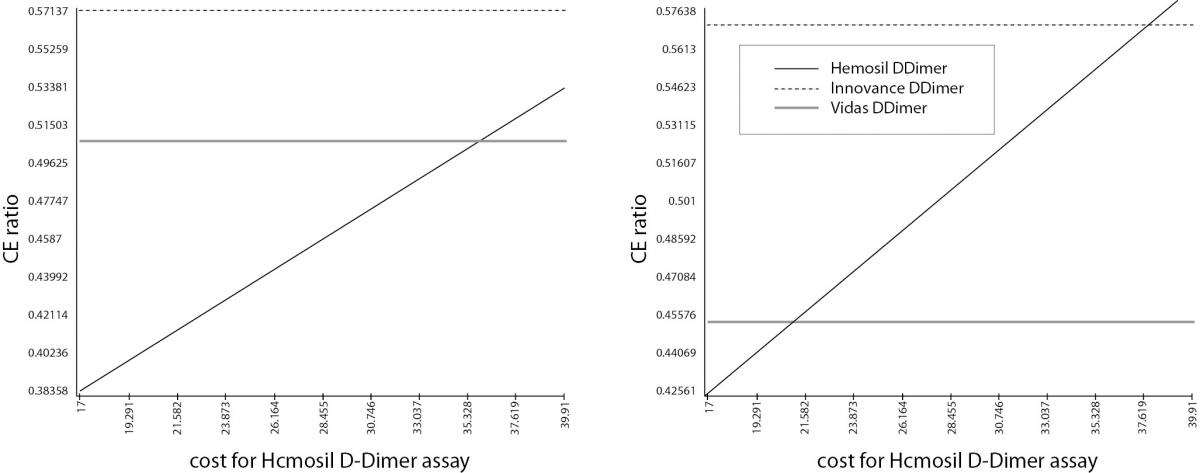

To examine the robustness of the results we performed sensitivity analysis by varying the average cost per patient using the service when 1 patient and 10 patients are admitted at the vascular ambulance per day (Table 1). According to the sensitivity analyses, results were sensitive to the change in the cost of the Hemosil D-dimer HS assay. The Vidas D-dimer Exclusion II assay gave the lowest ICER, but the Hemosil D-dimer HS assay was the most cost-effective alternative at cost values below 36 Euros in the first DAM and below 21 Euros in the second DAM, Figure 2a and 2b. This means that the Hemosil D-dimer HS assay was the most cost-effective alternative if the cost of the assay was dropped below 21.5 Euros (base case analysis 27.72 Euros) for both DAMs. Furthermore, if only one patient was admitted to the vascular ambulance per day for the first DAM, Hemosil D-dimer HS assay was the most cost-effective alternative.

Figure 2. Sensitivity analysis. Panel A) Sensitivity analysis for the first DAM; Panel B) Sensitivity analysis for the second DAM. Sensitivity analysis shows that the results were sensitive to the change of the Hemosil D-dimer cost. If the cost values for Hemosil D-dimer were changed (below 36 Euros in the first DAM and below 21.5 Euros in the second DAM), this assay becomes the most cost-effective strategy.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess the three different D-dimer measurements followed by CUS examination against the same three D-Dimer measurement and CUS examination in combination with PTP assessment. A CMA was applied since the data of the alternatives under investigation indicated an equal number of patients with DVT diagnosis but revealed significant variation in the number of patients selected for CUS and D-dimer testing and accordingly different economic burden. In addition, ICER analysis was applied since all three D-dimer measurements had different effectiveness. The scope of the analysis was focused on the financial consequences for the third-party payer - RIHI (CMA) and the clinical laboratory in hospitals (ICER analysis).

From all the diagnostic strategies in both DAMs the Vidas D-dimer Exclusion II measurement was the most cost effective alternative when more than one patient were admitted at the vascular ambulance per day. However, the Hemosil D-dimer HS assay could significantly reduce clinical laboratory costs when one patient was admitted at the vascular ambulance per day for the first DAM. The advantage of the Vidas D-dimer Exclusion II assay over other tests is faster DVT screening. Vidas D-dimer Exclusion II test, in conjunction with PTP scoring, safely excludes DVT in outpatients in 20 minutes. Use of this test dramatically cut D-dimer turnaround times, to 30 minutes from about 2 hours (21). The use of the Vidas D-dimer Exclusion II assay allows a doctor to quickly exclude diagnosis of DVT without waiting for costly and time-consuming imaging studies.

Contrary to the results of ICER analysis in the CMA in our study the best alternative for DVT screening was the alternative that employed Hemosil D-dimer HS measurements in combination with PTP scoring and CUS utilisation. This alternative saved 1.66 Euros per patient than the alternative which employed the Vidas D-dimer Exclusion II measurement. We suppose that additional costs per patient could be compensated by faster DVT screening and shorter length of stay in vascular ambulance when the Vidas D-dimer Exclusion assay was used. This could be very important for immediate therapeutic intervention which would save future healthcare costs.

Our study found significant cost-savings for the third-party payer from a reduction in the number of imaging tests after applying the second DAM for DVT screening. In comparison of two DAMs, the most prominent savings were observed with Innovance D-dimer (more than 11 Euros per patient). The savings are not so prominent in case of Hemosil D-dimer HS and Vidas D-dimer Exclusion II (Table 3) due to the fact that even 34 patient hadn’t D-dimer analysis, CUS was performed for two more patient which is four times costlier procedure than D-dimer analysis. Our results on savings are in accordance with findings from several studies already published in the literature (22-25) and indicate the advantage of the second DAM against the first as it fulfils to a greater degree the criteria of clinical effectiveness and economic efficiency. Perone and colleagues (26) used decision analytic modelling to compare four strategies, incorporating combinations of clinical risk scoring, D-dimer and ultrasound, with a ‘no treatment’ alternative. They estimated that the cheapest alternative (combining clinical risk scoring and D-dimer with a single ultrasound) was also the most cost-effective. This alternative was similar to the second DAM in our analysis. However, it can be argued that no significant opportunity cost was lost as a result of PTP score calculation. There is a possibility of minimal costs associated with time spent on recording the answers to nine questions for the PTP score questionnaire. This extra time of about 2–5 minutes was too small to significantly change the costs of the strategies. Moreover, the results of other studies confirmed advantage of using PTP score before D-dimer mesaurement and CUS utilization in practice. Van Belle et al. (27) investigated more than 3000 symptomatic patients and found that the combination of a low PTP with low D-dimer effectively excluded pulmonary embolism, with only a 0.5% incidence of DVT in 3-month follow-up. Howeever, Sartori et al. evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of PTP score and D-dimer assay for isolated distal DVT. According to their results, D-dimer had a better NPV than PTP, but neither of these analyses had sufficient diagnostic accuracy for isolated distal DVT. However, in patients with low PTP, D-dimer had a negative predictive value of > 95% for isolated distal DVT (28).

The study is representative to the vascular ambulance at Department of Clinic for Vascular Surgery, Clinical Centre of Serbia. In the absence of national or state-wide data on the number of outpatients with DVT presenting at an emergency vascular department, we have estimated annual national savings on the assumption that the clinic is representative of public hospitals with a vascular department. From a third-party payer perspective, the annual cost savings for 1000 patients with suspected DVT is about 11,480 Euros if the best screening alternative was used in comparison to the worst alternative. The total number of patients with clinically suspected acute DVT at the vascular ambulance at Department of Clinic for Vascular Surgery, Clinical Centre of Serbia is approximately 2500. The projected savings for Clinical Centre of Serbia are 28,700 Euros. However, Mahan et al. developed a decision tree and cost model to estimate the United States (US) health care costs for total DVT, total hospital-acquired DVT, and total “preventable” DVT. Annual total DVT cost ranges in 2010 were $7.5 to $39.5 billion (5,6 to 29.9 billion Euros). When the sensitivity analysis was applied (taking into consideration higher incidence rates and costs) annual US total DVT costs ranged from $9.8 to $52 billion (from 7.42 to 39.36 billion Euros) (29).

Conclusion

Our results support the feasibility of using PTP scoring and D-dimer measurement as the first step in DVT screening from a clinical laboratory and a third party payer perspective. In times of tight economic resources, the introduction of PTP scoring before D-dimer measurement and CUS utilisation would be highly convenient because it is simple to perform. Similarly, implementation of the faster D-dimer test is feasible not only for a clinical laboratory but also from a third-party payer perspective. Our study illustrated that the use of ICER enables laboratories to choose optimal laboratory tests according to number of patients admitted to laboratory and it could be a part of integrative approach to DVT diagnostics. In addition, analytical evaluation could help to understand where and how cost can be restrained.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Education and Science, Republic of Serbia (Project No. 175035). The authors would also like to thank Dr. David R. Jones for help in editing the manuscript.