Introduction

Preanalytical phase covers the wide range of activities, like patient preparation, blood sampling, sample transport and it is the source of the majority of laboratory errors (1,2). Proper patient preparation is a key prerequisite for ensuring the quality of the sample. To minimize the total preanalytical variability, for most of the biochemical analyses, patients should be in the fasting state prior to the blood sampling (3). Fasting state influences not only biochemical analyses, but also other types of laboratory tests like haematological and coagulation analyses (4,5).

There is a significant influence on several laboratory tests after a regular meal. That is an important reason for standardization of the fasting time for all laboratory tests. Thus, it could be possible to prevent false results (6).

Moreover, beside lipemia, patients’ variables including exercise, diet, age, sex, obesity, stress, smoking and medication may affect laboratory test results. It influences alteration of various metabolic, endocrine, oxidation and others mechanisms and the concentration of parameters is completely changed (7-9).

Furthermore, non-fasting state influences the results of laboratory test which use transmission of light as part of their measurement system because of three distinct mechanisms: light scattering, increasing non-aqueous phase and effects of partition between polar and non polar phases (10).

In laboratory, our instructions on patient preparation are that fasting samples are taken in the morning between 7-9 a.m. after 12 hours of fasting. During the fasting period only water consumption is allowed (3). This information is provided on the laboratory web page, as well as in the written form, as a leaflet which can be obtained in the laboratory. It is important to mention other resources of information (physicians, television, etc.). Furthermore, it is usually too late to provide the information about the patient preparation, once patient has arrived to the laboratory. Due to that reasons, our hypothesis was that many patients are not familiar with the instructions issued by the laboratory and are not adequately prepared for blood sampling, when they arrive to the laboratory.

With this study we have therefore aimed to explore: i) how well patients are informed about the fasting requirements for laboratory blood testing; ii) the preferred way by which patients are informed about how to prepare themselves for laboratory testing; and iii) whether patients arrive to the laboratory for phlebotomy properly prepared.

Materials and methods

Subjects

This observational survey was conducted during February 2013 in a primary care medical laboratory. The laboratory is not accredited according to ISO 15189 norm. Total number of samples admitted to the laboratory is 450 per day.

An anonymous questionnaire (Table 1) was conducted on a consecutive sample of 150 outpatients older than 18 years, who were admitted to the laboratory in the morning between 7-9 a.m. for routine blood testing. The response rate was 89% meaning that out of total of 166 patients, 16 patients did not agree to participate in the survey. The patient’s request form was examined by the laboratory staff and only those participants who had test requests for which fasting was required, were included in this survey. All patients were informed about details of the questionnaire and consented to participate in the survey.

All subjects who have consented to this survey were asked about their basic demographic data (e.g. age and gender). Out of 150 study participants, there were 88 (59%) female patients. The demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

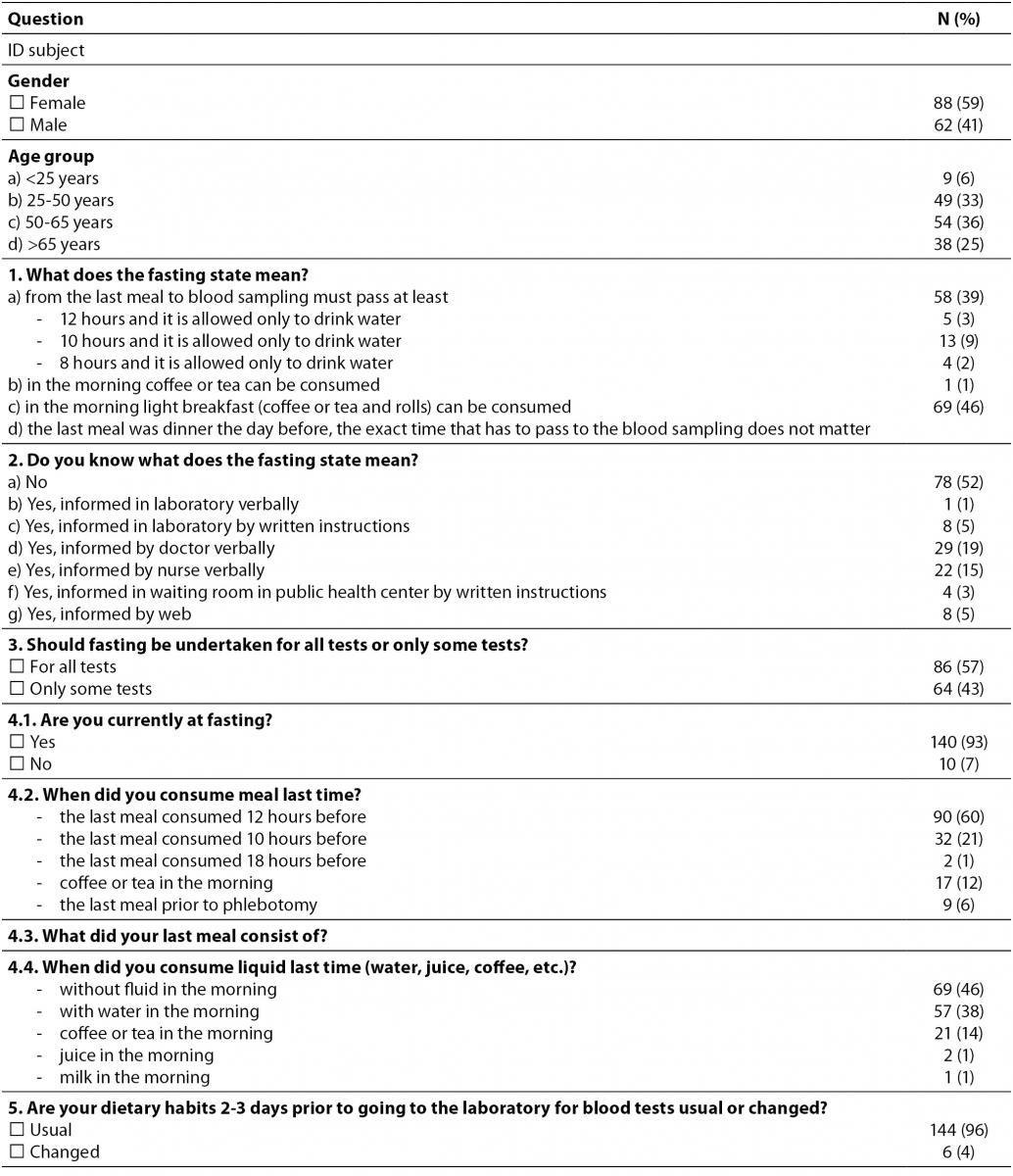

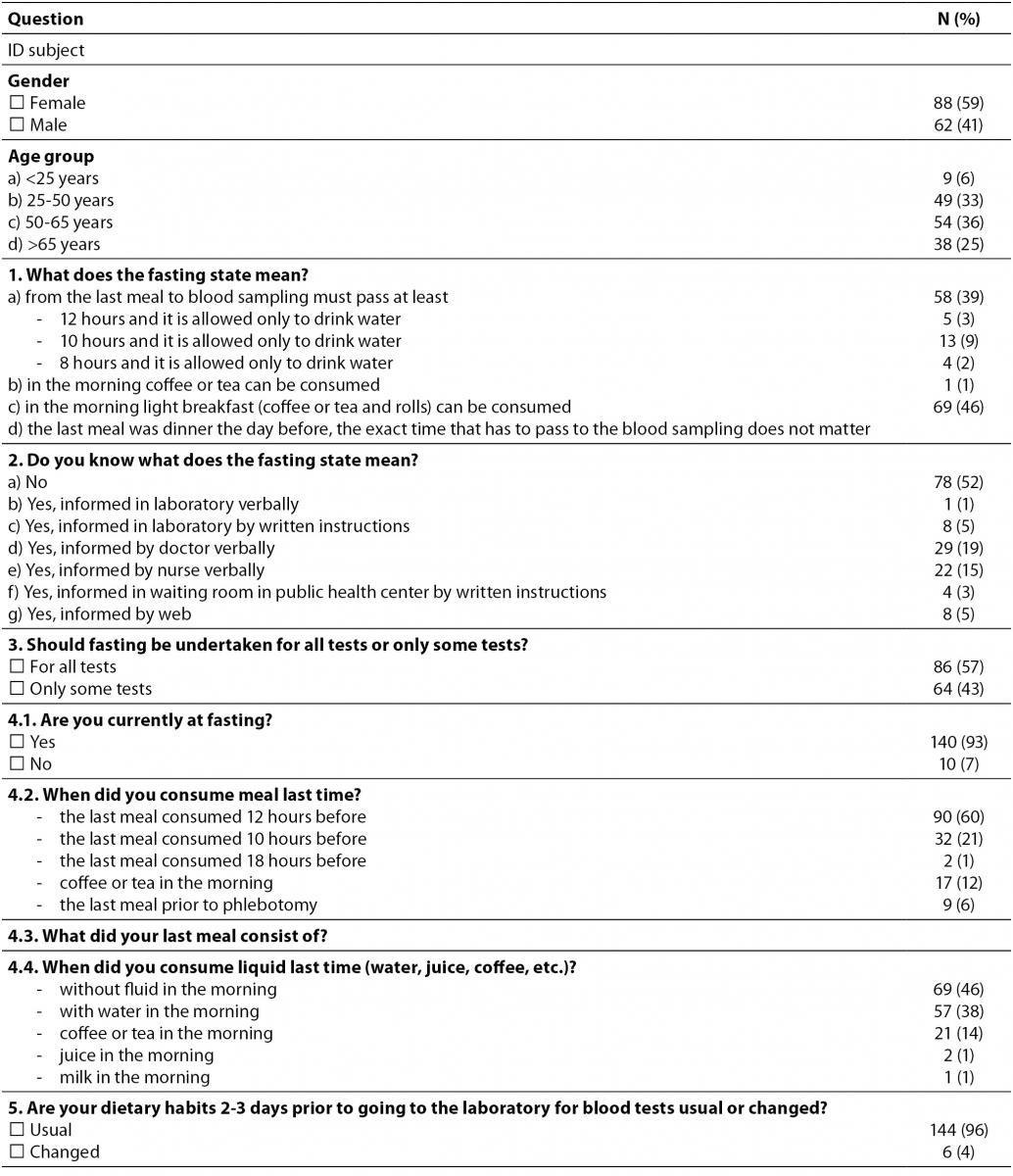

Table 1. The questionnaire used in the survey about how patients are informed of proper preparation for phlebotomy (N = 150).

Methods

Patients were interviewed by the laboratory staff. The questionnaire consisted of 5 questions which relate to the following issues: 1) definition of the fasting state, 2) how and who the patients got information about proper preparation for laboratory testing from, 3) if the fasting state is important for all laboratory tests or not, 4) whether patients arrive to the laboratory properly prepared for phlebotomy, and 5) whether patients change their dietary habits 2-3 days before they go to the laboratory for blood testing.

Fasting is requested for serum concentrations of tryglicerides, albumin, iron, total calcium, phosphorus, creatinine, total and direct bilirubin, C-reactive protein, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, uric acid, total protein, sodium, potassium, magnesium, haematological and coagulation parameters (4-6,11).

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as counts and percentages. Differences between groups were tested by Chi-squared test. When the Chi-squared test conditions were not met, Fisher’s exact test was used.

Statistical analysis was performed by using MedCalc 12.3.0.0 statistical software (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium). P < 0.05 was set as the level of significance.

Results

When they were asked about the correct definition of the fasting state (12 hours before blood testing there should be no food intake, but only regular water intake), only 58 patients (39%) stated that they were fully aware of that definition. Almost half (46%) of the studied group believed that the exact time of the last meal was not important, as long as the last meal is on the day preceding the blood sampling. Other data on this question are presented in Table 1.

Significant is that 57% of the participants believed that fasting is required for all laboratory tests.

Furthermore, 78 patients (52%) were not informed at all about the requirements for proper preparations for blood testing, while 72 patients (48%) were only partly informed about proper preparation. “Partly informed about proper preparation” means that patients were without fluid/water intake or last meal in less than 12 hours prior to blood sampling. Those who claimed to be aware of the requirements for fasting, stated that they obtained the information i) verbally in laboratory (1%), ii) by reading the written instructions issued by the laboratory (5%), iii) from a physician (19%) or nurse (15%), iv) from written instructions in waiting room in public health center (3%) or v) from the Internet (5%).

Unfortunately, patients who received instructions from a physician or a nurse stated that they were only informed that they need to be in the fasting state for blood sampling, but without any explanation what the fasting state actually means.

Only 90 of total study group (60%) arrived to the laboratory properly prepared for the laboratory blood testing, i.e. their last meal was 12 hours before the arrival to the laboratory. Furthermore, 32 subjects (21%) had their last meal 10 hours before they arrived to the laboratory, 2 subjects (1%) had their last meal 8 hours before they arrived to the laboratory, whereas even 9 patients (6%) were not in the fasting state. Those patients have had their breakfast in the morning, shortly before the blood sampling. Other data are showed in Table 1.

Interestingly, the ratio of patients who arrived to the laboratory prepared properly, did not differ between those who were given partly instructions and who were not given any instructions (47/72 (65%) vs. 43/78 (55%) patients, P = 0.333, respectively).

Therefore, a proportion of patients who were properly prepared, did not differ from subjects who believed that fasting is required for all laboratory tests and those who considered the opposite (51/86 (59%) vs. 39/64 (61%) patients, P = 0.840, respectively).

Furthermore, 144 subjects (96%) did not change their dietary habits 2-3 days before going to the laboratory for blood testing.

Discussion

With this study we show that a substantial proportion of the patients do not have enough information about adequate preparation for laboratory tests. A large portion of patients is not familiar with the requirements for the fasting state. Patients are not very likely to seek for information about how to prepare for the laboratory testing. Majority of patients who received some kind of instructions for laboratory testing, claimed that their major source was a requesting physician or a nurse. The most striking finding was the fact that knowledge about the importance of fasting did not influence the patient behavior, i.e. patients who believed that fasting is required for all laboratory tests were not more likely to arrive properly prepared, to the laboratory, compared to those who considered the opposite. Moreover, patients who have received partly instructions were unfortunately not more likely to arrive to the laboratory prepared properly, compared to those who did not receive any instructions.

In the recently published study by Kljakovic et al. (12) it has been shown that patients were more likely to be properly prepared for the laboratory testing if they knew their requesting general practitioner.

The fasting state and patient preparation generally are very important because it could significantly interfere in during analysis the most parameters. It is, therefore, generally recommended that patients avoid high-fat food and do not eat or drink anything except water for a minimum 12 hours prior to the arrival to the laboratory (3). Proper preparation of patients for blood sampling is of vital significance for the quality of the sample and test results (4,5). The majority of medical decisions are based upon results obtained from the laboratory and because of that it is crucial for patients to get the most accurate information.

Unfortunately, as our data indicate, it seems that patients are not well informed about the need for fasting, fasting requirements and definition of fasting.

The lack of knowledge and poor education is a shared responsibility of all stakeholders involved in the total testing process: requesting physicians, nurses, laboratory professionals and patients. The recent report issued by the European Commission shows that the level of communication between patients and their physicians was unsatisfactory low. The lack of physicians’ time was identified as the main barrier to the effective communication. The quality of communication between patients and health care workers and the amount the time spent with the patient were identified as the major area of potential improvement (13).

Laboratory professionals are responsible for the management of the quality of the preanalytical phase. Although much of the activities occur outside of the laboratory and beyond the direct supervision of the laboratory staff, it is the responsibility of the laboratory professionals to continuously improve the preanalytical practices and activities (14).

Laboratories need to have updated, clear and understandable written instructions for the preparation of patients prior to arrival at the laboratory, depending on the type of the required tests. Those instructions need to be available on-line and disseminated to all users of laboratory services.

Laboratory experts are also responsible to educate physicians about the importance of the proper patient preparation and should try to motivate physicians to improve the way they inform patients about the fasting requirements.

This questionnaire can become good quality indicator in the laboratory. Thus, the laboratory staff would able to systematically monitor frequency of visits to the laboratory of patients with lack of information about preparing for phlebotomy. Based on that, corrective actions could be introduced in order to improve informing of the patient about the proper preparation for laboratory testing.

Finally, laboratory personnel task is also to raise the public awareness about the importance of the preanalytical phase and its influence on the quality of the sample. By doing so, the laboratory personnel will be able to reach patients and motivate them to seek available information when they come to the laboratory next time.

Only by joint effort of all stakeholders involved, a common goal shall be reached – an educated patient aware of the fasting requirements and motivated to adhere to the laboratory instructions.

Conclusions

Based on our observations, substantial proportion of patients do not come properly prepared for laboratory testing. We conclude that patients are not well informed about the fasting requirements for laboratory blood testing. Moreover, requesting physician is the preferred source of information from which patients learn how to prepare themselves for laboratory testing.

We believe that it is the responsibility of laboratory professionals to educate requesting physicians about the importance of the proper patient preparation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Ministry of Science, Education and Sports, Republic of Croatia, project number: 134-1340227-0200.

The authors also wish to thank to all study subjects who filled out a questionnaire and thus showed interest and the importance of improving the quality and enabling the implementation of this research.