Introduction

A shift in the carbohydrate composition of transferrin towards glycoforms with a lower degree of glycosylation is frequently observed in alcohol abuse (1). Carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT), indicating collectively the glycoforms of human transferrin with 0-2 terminal sialic acid residues, namely asialo-, monosialo- and disialotransferrin, is considered the most specific biochemical marker for detecting chronic alcohol abuse and for monitoring abstinence during treatment (1). Because of its application to the legal medicine context, such as workplace safety monitoring or in traffic medicine, where a positive result may hamper driver’s license renewal or regranting, many studies have investigated the factors possibly associated to CDT false positivity or CDT specificity (2-4). To overcome the lack of standardization still affecting CDT analysis (5), the Working Group on Standardization of CDT measurement (IFCC-WG-CDT) has suggested to use disialotransferrin (DST) as the primary target molecule for CDT testing, measured by HPLC and expressed as relative amount (%CDT) of total transferrin to compensate for variable levels of total transferrin concentration (6). Accordingly, studies assessing CDT by HPLC, and following IFCC-WG-CDT recommendations, have shown that many of the physiological and pathological factors previously supposed to affect CDT specificity were indeed due to unspecific methodologies applied for CDT analysis (3).

Conversely, CDT sensitivity still remains a controversial issue with only a minority of studies reporting on factors associated to false negative results in chronic alcohol abusers.

Although drugs could theoretically affect CDT, few studies have investigated the role of pharmacological therapy on CDT levels (7); in particular, while enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs were reported to increase CDT, angiotensin II receptor antagonists (sartans) have been shown to lower CDT values (3,8). However, major limitations of these studies include under-reported alcohol consumption, use of a single determination of the biomarker and unavailability of clinical data. The study of the possible influence of pharmacological therapy on CDT levels could be valuable in many situations: among others, CDT is used to detect chronic alcohol consumption in subjects applying for driver’s license renewal or regranting and a growing number of people, mainly in the elderly, are now under polytherapy; moreover, CDT is frequently used to assess patients suffering from alcoholic cirrhosis, and often under polytherapy, as potential candidates for orthotopic liver transplantation.

Aim of this study was to report on the possible effect of the pharmacological therapy on CDT levels in a chronic alcohol abuser, with known medical history (July 2007 – April 2012) and alcohol abuse confirmed by relatives.

Materials and methods

Subject and samples

The patient investigated in this study is a male, 65 years old, body mass index = 26.8, former smoker (more than 20 years of abstinence), with an history of mild hypertension (therapy with ramipril discontinued), gastric ulcer, without clinical evidence of liver cirrhosis or fibrosis. Alcohol consumption (beer: > 1000 mL per day and wine: 500-1000 mL per day) has been frequently witnessed and reported by family members and neighbours and has been estimated as 90-150 g ethanol per day.

Blood samples were collected in Becton Dickinson Vacutainer Plastic tubes (BD Diagnostics, Sparks, MD) containing the appropriate additive, while urine samples were collected in sterile plastic tubes.

Methods

CDT was measured by %CDT kit by HPLC (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany). Briefly, samples were prepared (pre-treatment includes iron-saturation with Ferric Chloride (FeCl3) and lipoprotein precipitation with dextransulfate) according to manufacturer’s instructions and 100 µL were injected in a Agilent 1200 HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) with anion-exchange cartridge kept at 40 °C, using a ternary buffer gradient with a flow of 1.4 mL/min and detection at 460 nm. After peak integration, CDT, calculated as the ratio between the area of the disialotransferrin glycoform and that of all transferrin glycoforms, was then expressed as percentage (%) of disialotransferrin to total transferrin area (9) (laboratory cut-off: 2.0%). The method does not allow estimation of circulating total transferrin levels. Two sets of controls (low control: 0.7-2.1%; high control: 2.6-4.4% also supplied by Bio-Rad) were run as triplicates, and always found within the range declared by the manufacturer. Total precision (CV%) at mean CDT levels of 1.14% and 6.25% was respectively 5.9% and 2.2%, with a recovery of 99% and a detection limit of 0.3%. This HPLC-based commercial kit was recently validated by Helander in comparison with the reference candidate method and found to be appropriate both for routine and confirmatory CDT analysis (9).

Aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) were measured on ADVIA 2400 (Siemens Healthcare, Milan, Italy). Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) was assessed by a XE-2100 apparatus (Sysmex Europe GmbH, Norderstedt, Germany). Ethanol was evaluated after collection by Axsym (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) and confirmed by headspace gas chromatography mass spectrometry (HS-GC-MS) (PerkinElmer, Santa Clara, CA). Ethyl glucuronide in urine (laboratory cut-off 0.5 mg/L) was assessed by DRI-EtG Enzyme Immunoassay (Microgenics-Thermo Fischer, Milan, Italy) on ADVIA 2400 (Siemens Healthcare, Milan, Italy). Analytical performances were evaluated by taking part to GTFCh Proficiency Test (Gesellschaft für Toxikologische und Forensische Chemie). An informed consent was obtained by both patient and relatives.

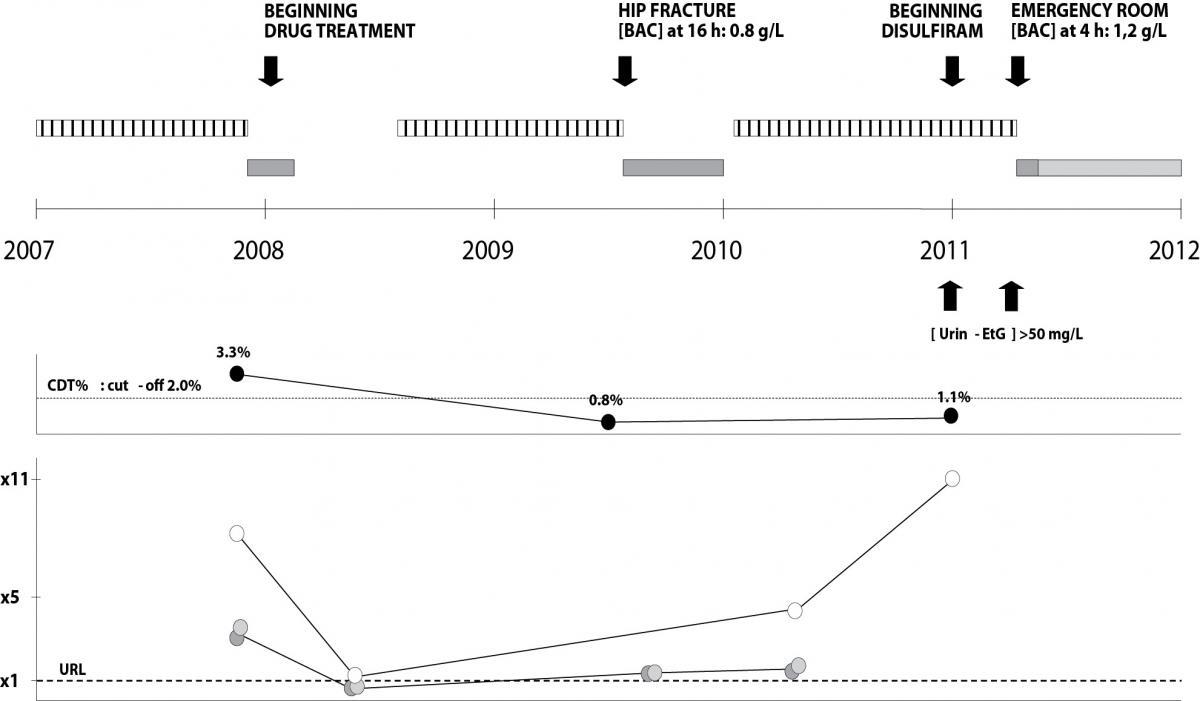

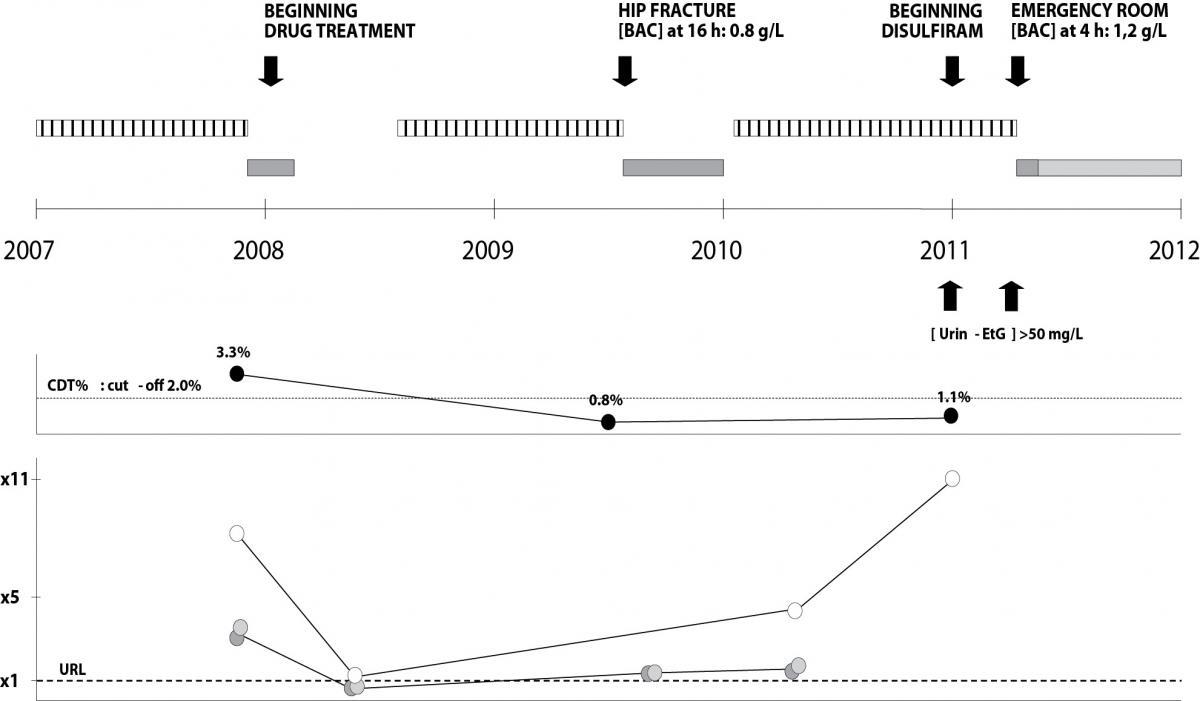

Figure 1. Medical history of the patient investigated.

Upper panel: clinical and therapy data (hatched, dark grey and light grey bars indicate respectively witnessed alcohol consumption, admission to hospital and admission to a private medical centre).

Middle panel: CDT trend in the period investigated (3.3% - 0.8% - 1.1%).

Lower panel: GGT (white circles), ALT (light grey circles) and AST (dark grey circles) trends in the period investigated. BAC (blood alcohol concentration) and urin-EtG (urinary ethyl glucuronide) concentrations were reported in the upper panel (arrows). URL indicates the upper reference limit for GGT (50 U/L), AST (40 U/L) and ALT (40 U/L). x 1, x 5, x 11 indicate respectively the URL, 5 and 11 times the URL.

Case history

The patient investigated in this study is a known alcohol abuser, whose alcohol consumption (90-150 g of ethanol/day) has been frequently witnessed and reported by family members and neighbours. At the end of 2007, the patient displayed following laboratory results: AST 137 U/L, ALT 120 U/L, GGT 434 U/L, MCV 101 fL and CDT 3.3%, confirming chronic alcohol abuse. On December 2007, after double coronary artery bypass surgery, he began a pharmacological permanent treatment with amlodipine (calcium channel blocker) 5 mg per day, perindopril (ACE inhibitor) 2.5 mg per day, atorvastatin (statin) 10 mg per day, isosorbide mononitrate (nitrate) 3 x 40 mg per day, carvedilol (beta blocker) 6.25 mg per day, ticlopidine (inhibitor of platelet aggregation) 250 mg per day (2009) changed to 2 x 250 mg per day (2010), pantoprazole (gastric acid pump inhibitor) 20 mg per day. After six months of reduced alcohol consumption (March to August 2008: normal aminotransferase activities and GGT slightly increased), he gradually resumed alcohol abuse; however, despite witnessed daily large alcohol consumption, on July 2009 the patient displayed CDT 0.8%. Two months later, the patient was admitted to the trauma service for a hip fracture after a fall; blood alcohol concentration, measured 16 hours after the admission, was 0.8 g/L, with aminotransferases slightly increased. Three months after discharge (March 2010), the patient displayed AST 58 U/L, ALT 72 U/L, GGT 229 U/L, MCV 95 fL. On January 2011, he was persuaded by the family to undergo, without notice, to CDT test: despite CDT negative result (1.1%), the patient displayed GGT 555 U/L, MCV 101 fL and concurrent significantly high urinary ethylglucuronide concentration (> 50 mg/L), measured three times a week for two consecutive weeks. One month later (February 2011) the patient decided to get help from Alcohol Rehab Center and to begin treatment with disulfiram. Despite increasing disulfiram doses, the patient continued to drink, as reported to the Rehab Center by family members and further confirmed by repeatedly elevated ethylglucuronide urinary concentration (still > 50 mg/L). On May 2011 the patient was admitted to the emergency service for acute coronary syndrome (ACS), displaying 4 hours after admission a blood alcohol concentration of 1.2 g/L. Finally, after discharge, he was transferred to a private medical center where he currently lives.

Discussion

According to many authors, one of the main pitfalls still affecting CDT testing is low sensitivity (10,11). Many factors have been reported to affect diagnostic sensitivity of serum CDT as a marker of alcohol abuse, namely age, sex, body mass, hypertension, drugs, smoking and drinking pattern (1). However, many contrasting data are available in literature and sensitivity of CDT still remains a controversial issue (12). A reason for this may be found in the plethora of analytical methods, cut-off and target molecules used to evaluate CDT in alcohol abusers (1,5,13-15).

Although this work is based upon a single clinical case, however it presents several strengths: CDT was measured with a HPLC method which has been recently shown to be appropriate both for routine and confirmatory CDT analysis (9); CDT, according to IFCC-WG-CDT recommendations, was reported as disialotransferrin (DST), the primary target molecule for CDT testing, and expressed as relative amount (%CDT) of total transferrin (6); the alcohol abuse was repeatedly witnessed by relatives and neighbours; it was documented by elevated CDT, ethylglucuronide and by high blood alcohol concentrations during several admissions to the emergency unit; finally it was confirmed by an Alcohol Rehab Center which even treated the patient with disulfiram. Moreover, both clinical history and therapy were available.

This study suggests the possibility that a medical therapy including different drugs may hamper the identification of chronic alcohol abusers by CDT. At least for this case, this effect does not depend either on irregular alcohol intake (common to subjects abstaining from drinking few weeks before CDT testing), as confirmed by relatives’ witness and concurrent elevated ethylglucuronide levels, or on analytical errors (sample substitution) or abnormalities (CDT variants), since CDT analysis was confirmed by a second analysis (different sample preparations) and performed by a validated HPLC method. Although circulating total transferrin concentration was not available, it is unlikely that the decreased CDT levels are due to decreased transferrin concentration, possibly induce by therapy or liver disease, since CDT was expressed as percentage of disialotransferrin to total transferrin area which allows for correction for variable transferrin concentrations. Moreover, the observation that the patient displayed elevated CDT levels before treatment (3.3%) but normal CDT levels in different occasions (0.8% and 1.1%) after treatment, despite unchanged alcohol consumption, suggests a link between CDT negativity and pharmacological therapy. Although detailed liver function data were not available (patient did not undergo liver biopsy during several hospital admissions), it is unlikely that CDT decrease was due to the presence of end-stage liver disease or cirrhosis, since it has been shown that these conditions may instead cause false positivite CDT results (actually in a very small percentage of cases if a validated HPLC method is used) (3).

Since little is known on the exact mechanisms by which alcohol increases CDT in chronic abusers (1), from a theoretically point of view it is possible that drugs may affect CDT levels by different mechanisms (8). However, the identification of these factors is behind the scope of this report, and requires a confirmation by both high-sample size studies as well as experimental studies in order to evaluate drug, dosage and possibly mechanism.

Recent data, obtained by validated CDT methods, suggest that, despite what has been previously reported in literature, only a minority of factors may lead to false positivity, namely liver diseases, pregnancy or glycosylation disorders (3,16). On the other hand, false negativity to CDT testing is still to be elucidated. With this regard, this clinical case, although with limited evidence, seems to indicate that, in addition to known factors (inappropriate methods, elevated cut-offs or patient’s abstinence in the weeks before testing) medical history could also play a role in CDT sensitivity, suggesting that there may be situations where the concurrent use, of additional alcohol biomarkers may help in properly identify alcohol abusers.