Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is highly prevalent global cause of mortality and morbidity (1). Up to 5% of patients are genetically predisposed to premature COPD due to the alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency (AATD) (2). This condition develops as the consequence of homozygosity or compound heterozygosity for the deficiency alleles of SERPINA1, gene encoding for alpha-1-antitrypsin (AAT). In contrast to the functional (M) alleles, these variants are associated with the reduced AAT concentration and functionality. Regarding prevalence, deficiency alleles are classified as common (Z, S) or rare (Mmalton, Siiyama, Mheerlen, Mprocida, null alleles etc) (3). Timely detection of AATD allows significant health benefits like AAT augmentation and genetic counselling. Nevertheless, it is estimated that only a minority (4-5%) of COPD patients with AATD are identified (2).

World Health Organization (WHO) and different pulmonologists’ associations advise measurement of AAT concentration as screening in COPD generally, with the special emphasis on targeted groups (i.e. those diagnosed with COPD before the age of 45, patients with family history of COPD). In case of decreased concentration, it is recommended to analyse patient’s pheno- or genotype (3).

Laboratory methods for testing AATD are associated with different limitations. Immunonephelometric assays provide data about AAT serum concentration, whereby different acquired factors (inflammation, hepatic or renal failure) significantly limit their reliability. In phenotyping, difficulties in interpretation and technical performance of thin-layer isoelectric focusing (IEF) can be encountered. For molecular techniques caution is necessary since rare alleles might not be detected unless standard genotyping is followed by sequencing. To overcome these issues and improve effectiveness of AATD testing, several centers have integrated methods and created laboratory algorithms for AATD detection (4-6). Following their experience, integrative algorithm was proposed with intention to increase AATD detection among Serbian patients. Algorithm starts with concomitant determination of AAT concentration and genotyping for Z and S alleles. IEF is performed as the reflex test to resolve discrepancies between the AAT concentration and associated genotype-concentration bellow 0.90 g/L and MM, 0.61 g/L and MZ or 0.84 g/L and MS genotype. Additional or bands with altered position in gel pattern indicate the presence of rare alleles, which has to be confirmed with DNA sequencing. If no specific bands are observed, the most probable cause of discrepancy could be attributed to acquired conditions affecting AAT concentration. Nevertheless, caution is needed in such situations to avoid neglecting of null allele presence and referring sample to DNA sequencing (7).

Considering the limited reliability of AAT concentration due to the effects of acquired factors, we hypothesized that an integrative algorithm could lead to the improved effectiveness by assuring AATD detection in heterozygous carriers with AAT concentration in reference range. The aim of our study was to analyse the effectiveness of an integrative laboratory algorithm for AATD detection in patients diagnosed with COPD by the age of 45 years, in comparison with the screening approach based on AAT concentration measurement alone.

Materials and methods

Study design

This cross-sectional study included patients from the Clinic for Lung Diseases in Clinical Center of Serbia, Belgrade. They were recruited from January 2011 till December 2013. Laboratory testing was performed in the Center for Medical Biochemistry in Clinical Center of Serbia and Institute of Molecular Genetics and Genetic Engineering, University of Belgrade. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Clinical Center of Serbia and all patients signed written consent.

Patients

The study enrolled fifty unrelated COPD patients (28 males and 22 females, 52 (24-75) years). Included were patients with the age ≤ 45 years at the time of COPD diagnosis in whom AATD presence was not investigated prior to inclusion in the study. COPD was diagnosed on the basis of spirometry measurements: ratio of postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC) less than 0.7 and FEV1 less than 80% (8).

Blood sampling

Venepunction was performed in the sitting position at 8 a.m., after the overnight fasting (9). Blood was collected in two Vacutainer® (BD Vacutainer, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) tubes - one SST® II Advance and one with 0.105 mol/L sodium citrate. Serum was separated after centrifugation for 15 minutes at 1500 x g and stored at -20 °С for up to 4 weeks. DNA was isolated with Illustra blood genomic Prep Mini Spin Kit® (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK), following manufacturer’s instructions, and kept at +4 °С.

Laboratory methods

AAT concentration was measured with immunonephelometry assay using N Antiserum to human α1-Antitrypsin (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Products GmbH, Marburg, Germany) on BN II® Nephelometer (same manufacturer). According to the manufacturer’s data, method reference range is 0.90-2.00 g/L, and within-run and between-run coefficients of variation were 1.8% and 1.2% at 1.46 g/L and 2.3% and 1.1% at 2.03 g/L respectively.

IEF was performed on precasted polyacrylamide gels plates (245 x 110 x 1 mm, Т = 5% & С = 3%, рН gradient = 4.0–5.0), under the conditions recommended by the manufacturer (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). Phenotype was analyzed through gel patterns comparison with commercial samples of known phenotype (Sebia, Evry Cedex, France).

Genotyping for Z and S allele was performed using the PCR-reverse ASO hybridization GenoType® ААТ kit (Hain Lifescience GmbH, Nehren, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR-direct sequencing was performed with the following primers: 5’-TGTCAATCCCTGATCACT-3’/5’-TTGCTTGTTTCTATGGGAAC-3’; 5’-GGTTTCTTTATTCTGCTACA-3’/5’-TCAGTCCCAACATGGCTAA-3’; 5’- GGCAGAAATAATCAGAAAAG -3’/5’- TGGTATCTGTAGGGAAGA -3’; and 5’- GTGACAGGGAGGGAGAGGA -3’/5’-GGAGGGATTTACAGTCACAT-3’ (Eurofins MWG Operon, Huntsville, AL, USA) for SERPINA1 exons 2, 3, 4 and 5. ABI Prism BigDye Terminator Kit v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit and Sequencing Analysis Software v5.2 Patch were employed according to manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific brand of Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

Statistical analysis

Absolute frequencies were presented for genotypes and ratios for allelic frequencies. AAT concentration was presented as median with range (min-max). Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U test with Boniferroni correction were used to compare AAT concentrations between groups of patients with different AATD status. Differences in number of detected AATD cases and carriers were tested using McNemar Chi-square test for dependent samples with exact P module. Data analysis was performed with statistical software SPSS® version 22.0 (IBM®, New York, USA, trial version). P value bellow 0.05 was considered statistically significant..

Results

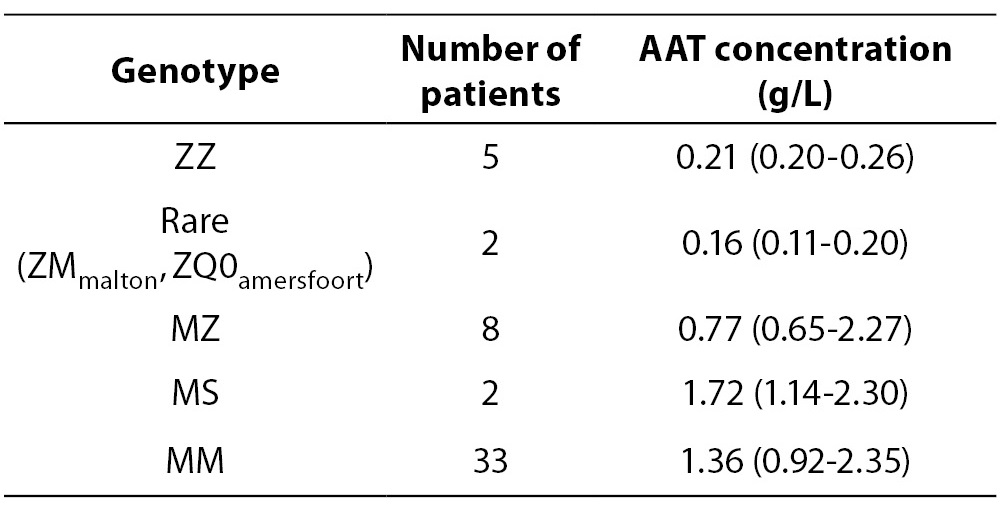

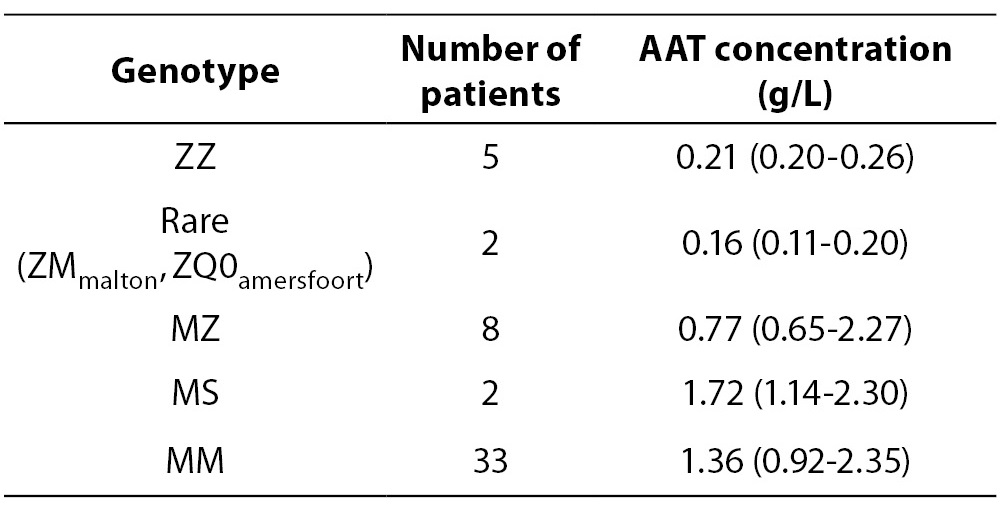

Data about detected genotypes and corresponding AAT concentrations are presented in Table 1. Calculated allelic frequencies were 0.2, 0.02 and 0.76 for Z, S and M allele respectively, while joint frequency of rare alleles was 0.02. AATD was detected in 7 and carrier state in 10 cases. AAT concentration in patients with AATD (0.20 (0.11-0.26) g/L) was significantly lower in comparison both with AATD carriers (0.96 (0.65-2.30) g/L; P < 0.001) and patients without AATD (1.31 (0.92-2.35) g/L; P < 0.001). In addition, no significant difference was observed between last two groups (P = 0.125), whereby the half of carriers (3 with MZ and 2 with MS genotype) had AAT concentration in the reference range.

Table 1. Detected genotypes and corresponding AAT concentrations.

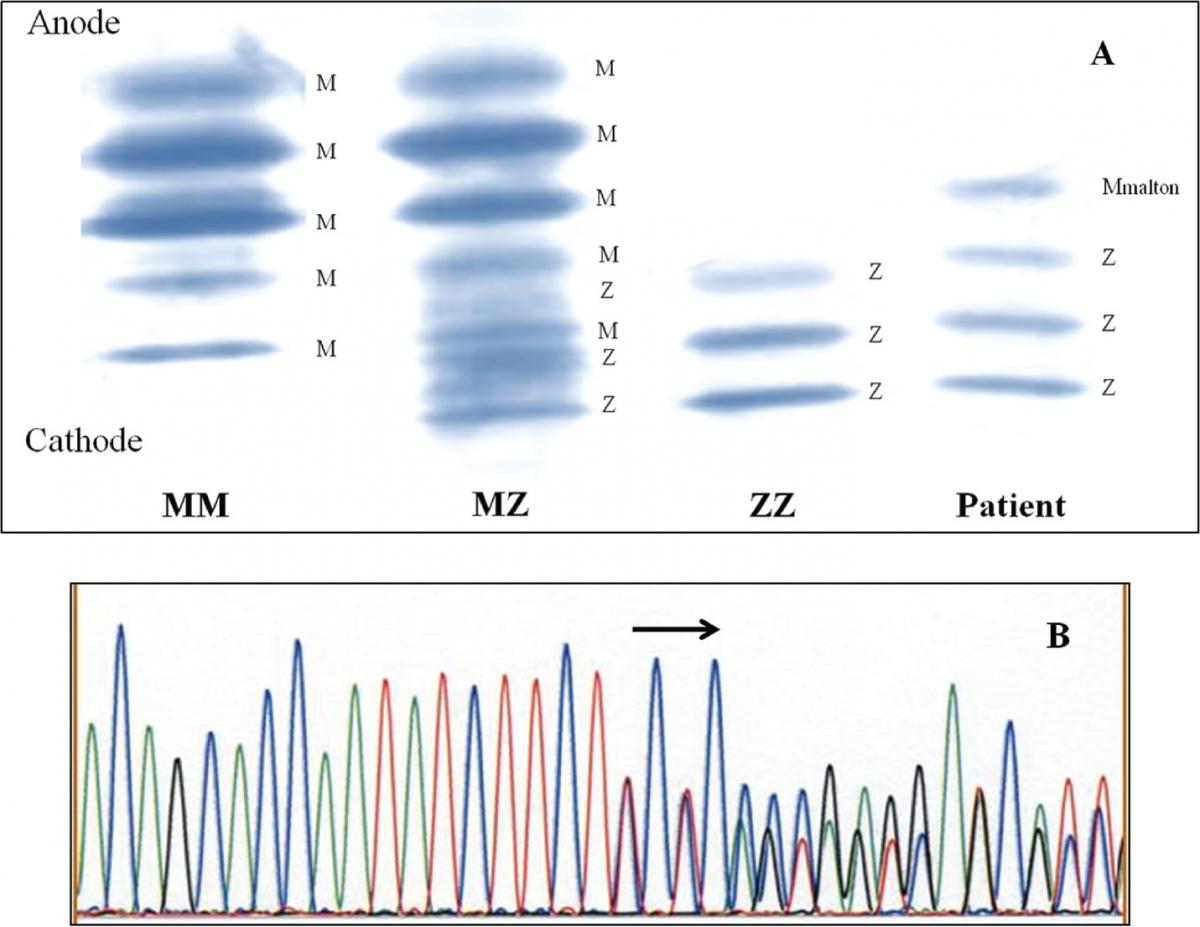

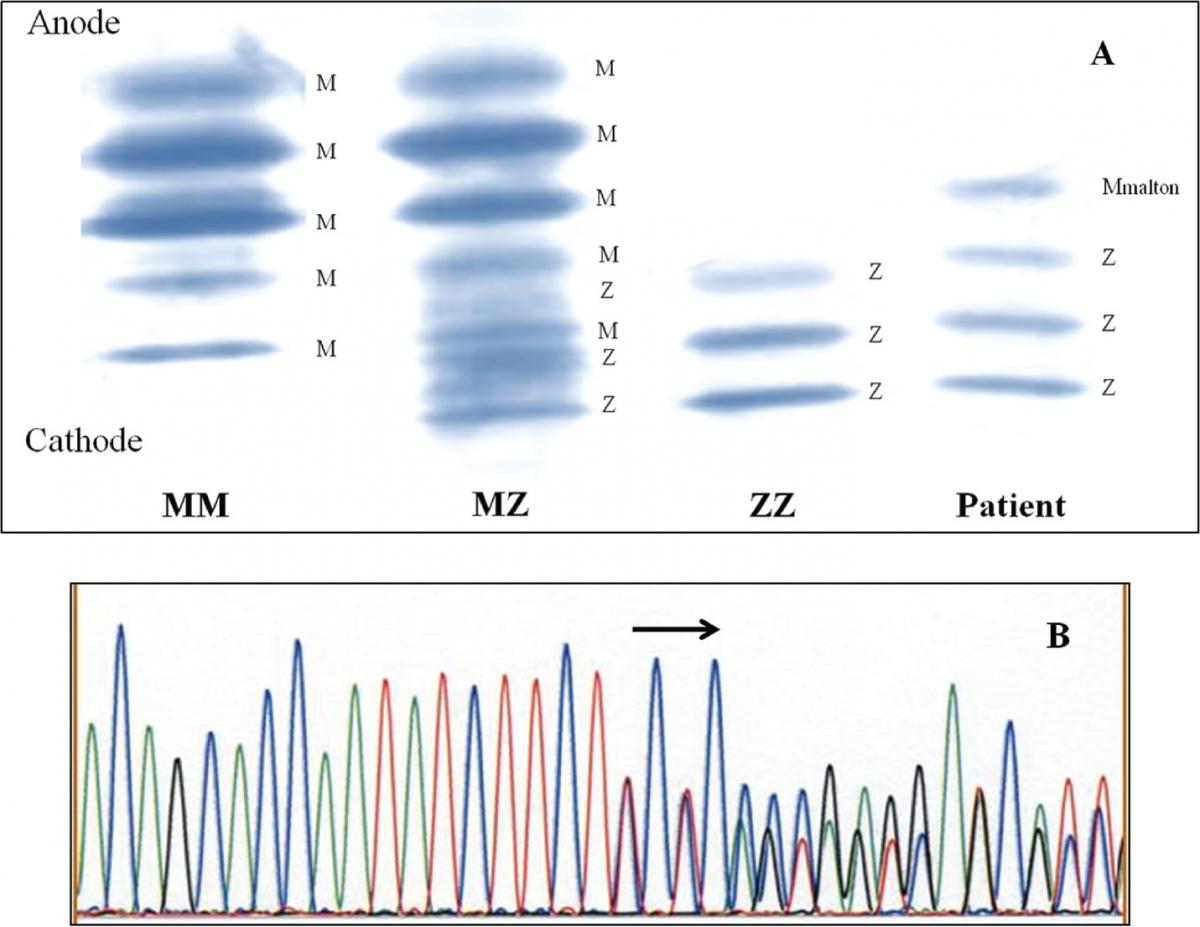

Figure 1. Identification of Mmalton allele.

1A - Determination of AAT phenotype in the patient and comparison to controls of the MM, MZ, and ZZ phenotype.

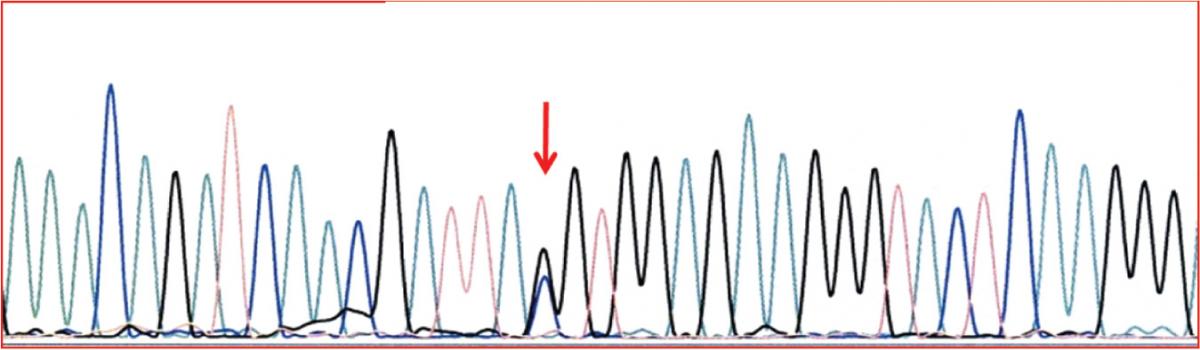

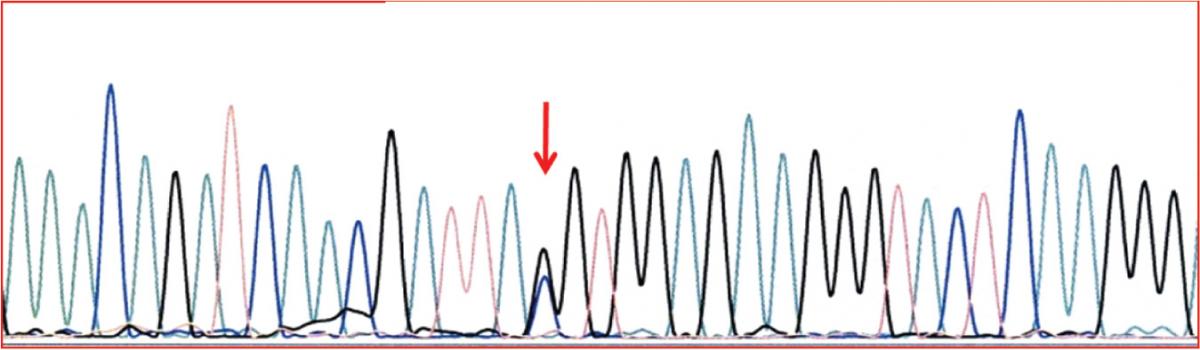

1B - DNA sequence of part of exon 2 in the SERPINA1, showing the heterozygous form of in- frame deletion of TTC codon for Phe75 or Phe76. Figure 2. Identification of Q0amersfoort allele.

DNA sequence of part of exon 2 in the SERPINA1, showing the heterozygous form of Tyr184TAC – stop184TAG.

The results obtained in the first diagnostic line were sufficient to evaluate the presence of AATD in 48 of enrolled patients. Discrepancy between immunonephelometry and results of genotyping for Z allele, was encountered in two cases.

Case 1: AAT concentration of 0.20 g/L was matched with MZ genotype. IEF pattern (Figure 1A) showed additional band positioned slightly cathodal compared with bands corresponding to M2 allele, thus indicative for Mmalton. The presumption was confirmed by sequencing (Figure 1B), leading to the conclusion that the patient was heterozygote for Z and Mmalton alleles.

Figure 2. Identification of Q0amersfoort allele. DNA sequence of part of exon 2 in the SERPINA1, showing the heterozygous form of Tyr184TAC – stop184TAG.

Case 2: AAT concentration of 0.11 g/L was measured and MZ genotype detected. IEF gel pattern contained no additional bands. The presence of null allele was suspected and confirmed by sequencing, which identified Q0amersfoort (Figure 2).

The difference in effectiveness of the screening approach in this group was estimated from the obtained results. Five carriers remained undetected and two AATD (compound heterozygotes for Z and rare alleles) could not be unequivocally determined. Nevertheless, the estimated effectiveness was not significantly different from integrative algorithm both for AATD (P = 0.500) and carriers (P = 0.063).

Discussion

Our study showed that integrative algorithm revealed rather high prevalence of AATD in a group of patients with premature COPD. Majority of affected subjects inherited Z allele homozygously, while compound heterozygosity with rare alleles was detected in two patients. In the half of the heterozygous carriers AAT concentration was in the reference range, indicating that they would be undetected by screening relying only on AAT concentration. Nevertheless the integrative algorithm was not shown to be more effective than screening based on AAT concentration alone, in the investigated group.

Previously reported AATD percentage in unselected COPD patients, ranging from 0.5 to 10.4 (10), was much lower than the prevalence obtained in this study. Additionally, in a group of randomly collected Serbian COPD patients AATD prevalence was found to be 2.9% (11) There is only one report on AATD prevalence among targeted COPD patients (premature emphysema, emphysema with no recognized risk factor, pneumothorax) which exceeded 40% (12). Taken together with the last example, our results might suggest that targeting on patients with premature COPD might be a useful mode to increase AATD detection rate. Nevertheless, this presumption has to be confirmed in a larger cohort of patients.

Previously reported overlapping between AAT concentrations corresponding to AATD carriers and patients with no AATD (3,6,13) was evidenced in the investigated patients. Through concomitant measurement of serum AAT concentration and genotyping for Z and S allele, integrative algorithm diminished the possibility that carriers remain undetected. It is noteworthy that this combination also improves diagnostic accuracy because genotyping for Z and S allele, if performed alone, might miss rare alleles (5,6,14). Regarding the investigated group, two patients might be erroneously classified as carriers of Z allele.

The reliable detection of rare alleles is very important criterion for algorithm application (15). Their presence was confirmed in two patients, one carrying ZMmalton genotype and the other ZQ0amersfoort. Mmalton is derived from the functional allele by the deletion of a TTC codon. Consequential lack of a phenylalanine residue potentiates protein aggregation in hepatocytes, while serum concentrations reach less than 15% of normal. The presence of this allele is associated with lung and liver disease (16). According to the currently available data, the index case with MmaltonZ genotype from this study is the second reported in Serbian population (17). Q0amersfoort is characterized by the nonsense mutation leading to the formation of TAG stop codon. Reliable data about clinical significance of this allele are not yet available (18). The index case with Q0amersfoort Z genotype identified in this study is the first report about this allele in patients of Serbian origin.

Rather small and preselected group of patients, recruited in a single institution is the main limitation of the study. In addition, the presence of additional COPD risk factors (smoking, air pollution exposure) was not considered during the recruitment. For these reasons the observed positive outcomes should be regarded as “pilot”. Moreover, they might explain why the integrative algorithm was not shown to be more effective than previously recommended screening approach based on AAT measurement. To resolve this issues further studies in larger cohorts of COPD patients, both unselected and targeted are recommended.

Conclusion

There is a high prevalence of AATD affected subjects and carriers in patients with premature COPD. The use of integrative laboratory algorithm does not improve the effectiveness of AATD detection in comparison with the screening based on AAT concentration alone.

Acknowledgements

The Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia supported this study on the basis of contracts No. 175036, 173008 and 175034. The authors are grateful to Prof. Svetlana Ignjatovic (Center for Medical Biochemistry, Clinical Center of Serbia & Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia), Marijana Dajak, Ph.D (Center for Medical Biochemistry, Clinical Center of Serbia, Belgrade, Serbia) and Dr. Nebojsa Dovezenski (LKB Vertriebs GmbH) for their valuable help, advices and suggestions.