Introduction

CD14, a cluster differentiation (CD) marker protein, is a multifunctional cell surface glycoprotein, which exists as a membrane-anchored form or in a circulating soluble form. The circulating soluble form of CD14 subtype (sCD14-ST), presepsin, is mainly used in acute care settings, such as emergency department and critical care, to distinguish between sepsis and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and for early detection of a possible bacterial cause (1-3). Recently it has also been proposed as a marker of the appropriateness of antibiotic therapy in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock (4).

The cutoff values of presepsin for distinguishing systemic bacterial and nonbacterial infectious diseases are usually very high, 600 pg/mL or over, in order to obtain a sufficient specificity. Different concentration levels of presepsin, regarding controls groups, have been variously reported in recent studies (5,6). Notwithstanding the fact that the traditional, widespread and practiced method for interpreting laboratory results is based on the comparison made with reference intervals (7), reference limits for this marker are not available at the moment.

The aim of this study is to determine the reference intervals of presepsin, according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) approved guideline C28-A3c (8).

Materials and methods

Subjects

Reference subjects were selected from the subjects seen at one of our blood collection centres for a complete blood count (CBC) test, over a period of one week, at the end of November 2013. All the individuals were fasting. Subjects were asked by one of us (MC) if they were free from fever, muscle aches, headache, weakness and not receiving antibiotics therapy. Further exclusion criteria were pregnancy, chemotherapy, and having test for infectious diseases, C-reactive protein (CRP) and/or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

Informed consent to use leftover plasma was obtained from all the participants at the time of blood sampling. Samples were collected between 7.00 and 10.00 am. Samples were made anonymous upon freezing, keeping only the information about age (in years) and gender.

Methods

For this study only leftover blood specimens, collected for a CBC test, were used. Blood samples were collected in endotoxin-free tubes containing ethylenediaminetetraacetate, in a K2EDTA Vacuette tube, 13 x 75 mm, 3.5 mL, Greiner, Bio-One GmBH (Kremsmünster, Germany).

Leftover plasma was recovered by centrifuging the K2EDTA tube at 3,000 x g for 10 min, at the end of CBC analysis, within 3 hours from collection. Separated plasma was immediately frozen at -70 °C until being assayed (stored for a month).

Presepsin concentrations were measured by a rapid, commercially available chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay (CLEIA) based on a noncompetitive CLEIA combined with Magtration® technology (9). The method was optimized on an automated immunoassay analyzer, PATHFAST™, Mitsubishi Chemical Europe GmbH, (Düsseldorf, Germany) (10). Total coefficient of variation (CV) of the method in plasma is declared to be between 3.8% and 5.0%, in a wide range of concentrations (11). Samples were measured over three consecutive days, using reagents from the same lot and the same calibration. A quality control assay (two levels) was performed after calibration to check the calibration curves and repeated at the end of the last sample.

Statistical analysis

Reference limits were calculated according to the non-parametric percentile method (CLSI standard C28-A3c) (8), since data was not normally distributed (evaluated by Shapiro-Wilk test). For the male subgroup the “robust method” was used as recommended by the CLSI C28-A3 guideline when samples sizes are small, with less than 120 data. The robust method has the appeal of the parametric method in that it does not require as many observations as the nonparametric procedure. With the robust method, the confidence intervals for the reference limits are estimated using bootstrapping (percentile interval method) (12). In bootstrapping, the data of the samples are used to create a large set of new “bootstrap” samples, simply by randomly taking data from the original sample (in this case, 10,000 iterations). Statistical significance was evaluated by the observation of lack in overlap of the CI of the reference limits.

Age related reference intervals were also estimated (13,14), by z-scores normal distribution analysis. Statistical analysis was carried out by using Medcalc® statistical software (v.14.8.1, Frank Schoonjans, Mariakerke, Belgium) (15).

Results

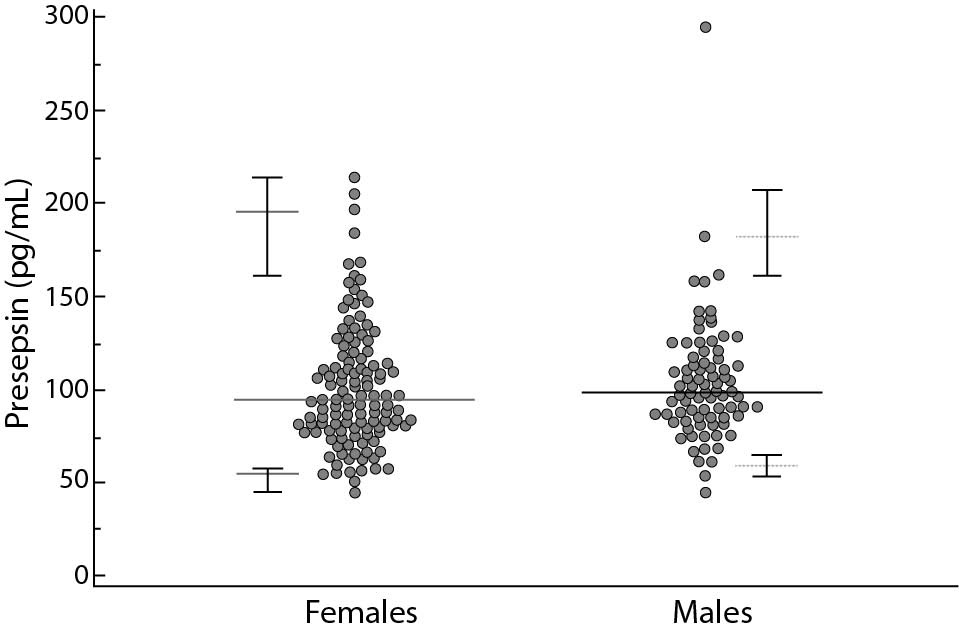

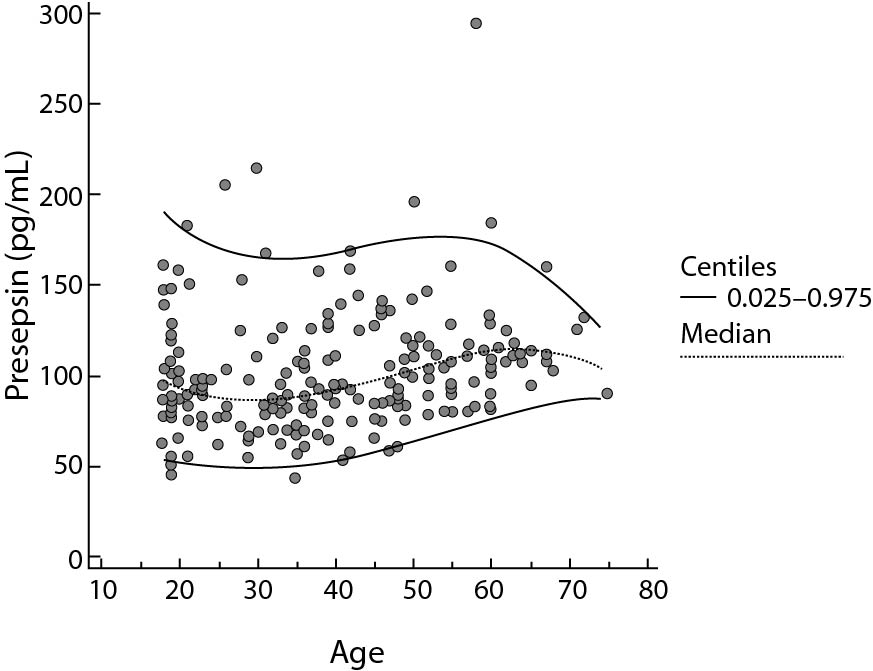

A total of 200 subjects were included in the study, 120 females and 80 males, aged 18-72 years and 18-75 years (median age 36 and 46 years), respectively. The reference limits for the presepsin were 55–184 pg/mL. The CI limits and the differences between female and male are summarized in table 1 and Figure 1. A relationship model between age and reference intervals is represented in figure 2. For ages 20, 30, 40, 50, 60 and 70 years the 0.025 and 0.975 centiles of estimated presepsin was 52-182, 49-165, 53-168, 63-176, 76-172, 85-143 pg/mL, respectively. A slight increase in the concentrations of presepsin is apparently associated with age. A reduction of inter-individual variability is observed after age 50, for both genders.

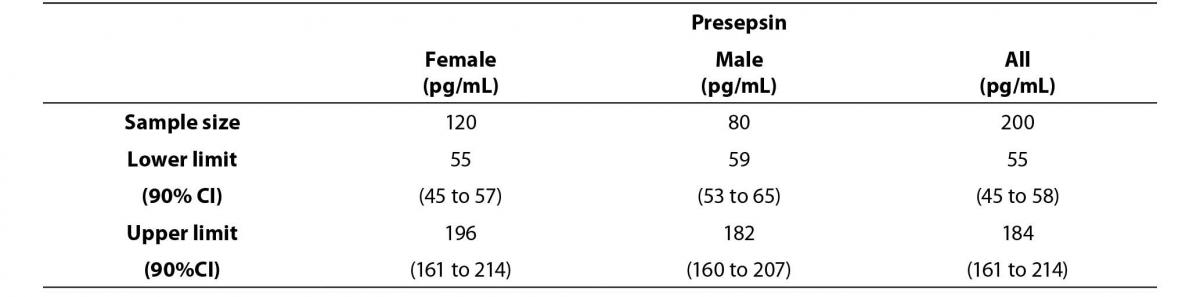

Table 1. 95% Reference limits for presepsin (pg/mL), according to non-parametric percentile method (CLSI C28-A3c) for females and all; for male subjects the “robust method” was used, as described in the same standard

Figure 1. Comparison graph of presepsin concentration levels between female and male reference subjects.

The middle line represents the median. Error bars represent the reference limits, calculated by the non-parametric percentile method percentile for females (continuous line) and by the robust method, according to the CLSI C28-A3c Standard.

Figure 2. Relationship between age and presepsin concentrations.

The continuous lines represent 0.025 and 0.975 centiles, the dotted line the median values.

Discussion

Data of this study show presepsin reference values 55 and 184 pg/mL, with negligible differences between males and females. Presepsin is normally present in very low concentrations in the serum of healthy individuals and it has been shown to increase in response to bacterial infections, according to the severity of the disease. Previously, other studies reported ranges of presepsin concentrations in control groups, compared to concentrations in patient groups with infectious diseases. Data from these studies are not univocal and different cut-offs were proposed for clinical use of this marker. Endo et al. reported a median value of presepsin concentration of 312 pg/mL, ranged between 71 and 9,036 pg/mL, in 70 patients admitted to the emergency room with not infectious disease. The authors determined an optimal presepsin cutoff value of 600 pg/mL to distinguish bacterial and nonbacterial infectious diseases (2). A cut-off point near 600 pg/mL was confirmed by Ulla et al. (16), with clinical sensitivity and specificity ranging from 0.79 to 0.87 and 0.61 to 0.81 respectively. Shozushima et al. reported “normal control” values of 294.2 ± 121.4 pg/mL, obtained from 128 healthy subjects (100 men and 28 women) assessed as controls. They also obtained similar sensitivity and specificity (0.80 and 0.81 respectively) to previous studies by using a lower cut-off, 415 pg/mL (17). Recently, presepsin was evaluated by Chenevier-Gobeaux et al. (18) in 144 consecutive patients at the emergency department (ED) without acute infection or acute/unstable disorder, and 54 healthy participants. In the healthy subjects the presepsin median concentration was 202 pg/mL (167-266 interquartile range), but the 95th percentile of presepsin values in the ED population was 750 pg/mL. The authors found a significantly increased presepsin concentration in patients aged over 70 years vs. younger patients (470 [380-601] ng/L vs. 300 [201-457] ng/L, P < 0.001). Prevalence of elevated presepsin values was increased in patients in comparison to control subjects (80% vs. 13%, P < 0.001), and in patients aged ≥ 70 years compared to younger patients (87% vs. 47%, P < 0.001). Presepsin concentrations were also significantly increased in patients with kidney dysfunction.

The variability of presepsin concentrations in the control subjects, which is observed in various studies, can depend on the selection bias of the “reference” subjects.

The availability of reference values for this marker might be of some interest, considering that new and less elevated discriminant decision levels were published recently (Liu et al., 317 pg/mL) (19), while other studies confirmed higher cut-offs (Romualdo et al., 729 pg/mL) (20).

We found the upper reference limit is 184 pg/mL. This limit is lower than the previous cut-off limits for sepsis, but also lower than the values obtained in control groups in other studies. The cut-offs proposed so far are derived from analysis of the best diagnostic efficiency of the test, in distinguishing between bacterial and non-bacterial infections in still critical patients. When healthy subjects, not affected by inflammatory diseases were considered, the maximum values of presepsin could be lower. Moreover it could also be due to the selection criteria of reference subjects and in the standardization of the pre-analytical conditions.

All our reference individuals were fasting, samples were collected between 7.00 and 10.00 in the morning, in a sitting position; any possible inflammatory process was investigated as exclusion criteria.

Lower and upper reference limits for female and male subjects showed overlapping 90% CI and the differences could be due to chance.

Lastly, concentration levels of presepsin are not even particularly influenced by age contrary to what was recently found in the ED population (18). Our data suggest that it is reasonable to adopt a single reference interval (21).

Specific decision levels are required to define diagnostic and prognostic roles of presepsin in different settings of inflammatory and infectious diseases. It was argued that presepsin could provide additional information to values of CRP and procalcitonin (PCT) in the early diagnosis of sepsis (22). CRP demonstrates high sensitivity but very low specificity. PCT has gained a significant diagnostic role in this field, but this biomarker tends to rise transiently in non-septic conditions and SIRS, e.g., invasive trauma, surgery, heatstroke and physical exercise. Several studies compared the presepsin diagnostic power to that of PCT in detecting sepsis in patients with a documented or suspected infection, demonstrating the ability to differentiate between patients with bacterial and non-bacterial infections (2,23).

The availability of reference values for presepsin concentration can help to distinguish and quickly rule out healthy subjects. It is also helpful in risk stratification and therapy monitoring, fields in which the role of presepsin has yet to be clarified.

One of the limitations of this study was not to have considered a more representative sample of elderly subjects and to have limited the analysis to individuals up to 75 years. Furthermore, in the selection of reference individuals, we did not evaluate diseases other than inflammatory pathologies (such as kidney diseases, metabolic disorders, etc.).

Nevertheless, we found very low concentrations of presepsin in the reference subjects, defining a unique reference interval for females and males and for every age group. The availability of reference values according to the CLSI C28-A3c approved guideline could be helpful for future evaluations of this new marker for sepsis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mitsubishi Chemical Europe, by means of Gepa Diagnostics for providing the assays for this study.