Introduction

Direct-to-consumer genetic testing (DTC GT) refers to genetic testing advertised and offered directly to consumers outside the traditional healthcare system. In line with tremendous progress in genetic/genomic research leading to more and more genetic tests with potential predictive health information, private companies have found their niche in DTC GT. In the last few years, numerous private companies are emerging offering genetic tests without adequate pre- and post-test genetic counselling and mostly with no or minor clinical validity and clinical utility. A diverse selection of such DTC genetic tests are currently being offered to the public, including non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) for Down syndrome, diagnostic tests for monogenic disorders, (preconception) carrier tests, tests for detecting predisposition to common complex disorders, pharmacogenomic tests, nutrigenomic tests, tests profiling a risk to addiction and ancestry tests (1,2).

Claims that private companies make about offered DTC genetic tests are often unsupported by scientific evidence, mostly exaggerated, and may generate false expectations regarding the benefits of testing and lead to unwarranted decisions on the basis of test results. In addition, there is mostly no medical doctor specialized in clinical genetics involved in DTC GT and it involves inappropriate genetic testing of minors (3,4). Individuals are not informed/counselled before or after taking the genetic test which is against all international recommendations and guidelines on genetic testing. Even more, testing of minors is not only against guidelines but also unethical.

Regulatory framework of DTC GT in Europe is not unified and national legislations are not present in most of the countries (1,5). On the contrary, only a few EU countries have addressed DTC GT in their national legislation. For example, France, Germany, Portugal and Switzerland have specified in their legislation that genetic testing can only be indicated and performed by a medical doctor and only after adequate genetic counselling and obtainment of consent of the person being tested. On the other hand, provision of DTC GT is allowed in Belgium and the United Kingdom. It is important to emphasize that these countries only regulate DTC genetic tests nationally and their legislations have no influence on DTC tests offered through world-wide-web from other EU countries or from USA. Therefore consumers can still be reached from other countries through internet offers. National legislation concerning DTC GT in Slovenia is currently being developed and Council of Experts for Medical Genetics has issued An opinion about Genetic Testing and Commercialization of Genetic Tests in Slovenia (6). On the other hand, when clinical genetic testing is indicated and ordered by medical doctor, this is a part of National health care system in Slovenia, and testing is covered by basic health insurance. Laboratories, that perform these tests, fulfil the rules set down in the document Rules on the conditions that must be met by laboratories to carry out investigations in the field of laboratory medicine, issued by Ministry of Health (7). Also, they are listed in the Orphanet directory of medical laboratories providing genetic tests (8).

The aim of our study was to analyse current situation in the field of DTC GT in Slovenia (types of tests, number of companies and their offers, marketing) and related legal and ethical issues.

Materials and methods

Searching for information

Internet search was employed to identify currently offered DTC genetic tests. Using Google search engine and key search term direct to consumer in combination with genetic testing, DNA testing/test, online DNA test, saliva DNA test, DNA kit, home DNA we searched national web pages. All retrieved sites and documents were checked in order to extract data. In order to avoid loss of information, two of the authors performed this search independently. Described searches were performed in the February 2014 and repeated in October 2014. The types of genetic testing offered, advertised benefits and aims as well as accompanying services were examined.

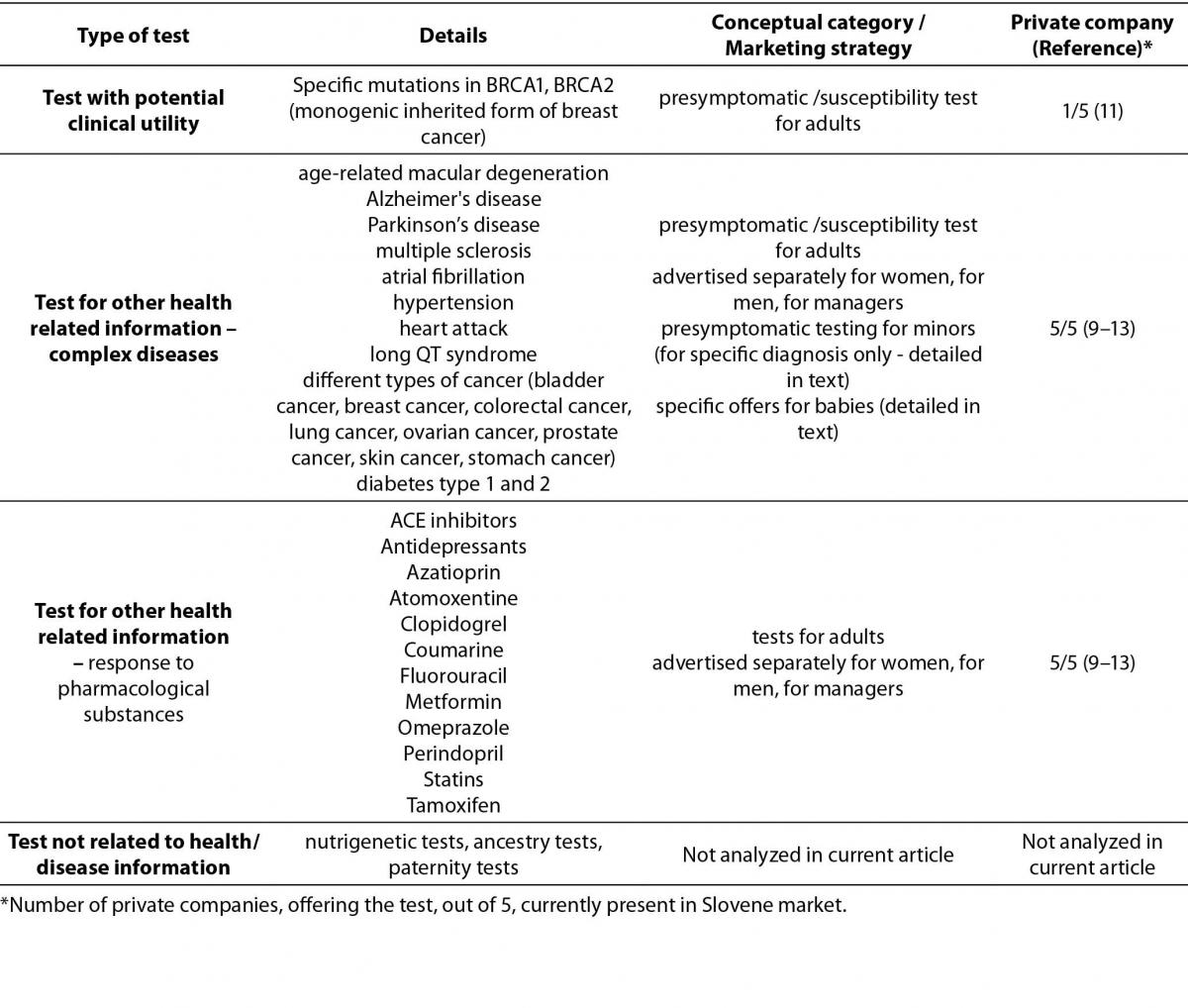

Types of genetic tests, offered directly to consumers

DTC genetic tests currently present in Slovenian market can be categorized in three groups for the purpose of this review: 1) the group of tests with potential clinical utility, such as testing for monogenic inherited form of breast cancer, BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes; 2) the group of tests with other health related information, such as test related to complex diseases or drug responses; 3) other DTC tests, such as nutrigenetic tests, ancestry tests, paternity tests, specific traits tests. Details on first two groups are presented in this review. The third group was not included in present analysis since we focused on genetic tests related to health/disease implications.

Results

Conceptual categories in which DTC tests are offered

The types and conceptual categories of DTC genetic tests in Slovenia are presented in table 1.

Table 1. Types and conceptual categories of DTC genetic tests in Slovenia.

The most represented group of tests is presymptomatic /susceptibility test for adults. These tests are usually advertised separately for women, for men, for managers and they involve susceptibility testing for number of adult onset diseases. As a result of DNA analysis the patient receives his/her personal report or personal genetic book with guidelines for preventive actions.

In addition, CardioRISQ test for assessment of risk for development of cardiovascular disease is offered by one private company (testing for 8 low penetrance mutations in 5 genes: ApoE (apolipoprotein E), MTHFR (methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase), FII (coagulation factor II), FV(coagulation factor V Leiden) and HFE (hemochromatosis)) (9).

Presymptomatic testing for minors is also offered, and it includes testing for susceptibility for celiac disease, lactose intolerance, diabetes type 1 and 2, obesity, heart attack, hypertension, osteoporosis. This category includes also DTC GT offers for baby or child packages where one can test his child for his genetic propensity to develop diseases (above mentioned) and also his genetically determined physical features (e.g. sports and orientation, learning from mistakes etc.), his development, talents and professional guidelines (10–13).

Another big group of test is DNA analysis for individual’s response to pharmacological substances used for therapy of depression, high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, diabetes and some other diseases. In addition, one of DTC providers subspecializes in cancer disorders (myRISK pathology supported genetic tests) and offers testing after diagnosis of breast cancer (prognosis indicators, response to treatment, risk of recurrence, types of cancer, level of estrogen, progesterone HER2 receptors) and testing after diagnosis of colorectal cancer (relapse risk assessment). Also, multiplex DNA test for individuals previously diagnosed with multiple sclerosis is offered, stating that it assesses genetic and lifestyle risk factors in relation to the metabolic profile of each patient, taking into account relevant gene-drug (pharmacogenetic) and gene-diet (nutrigenetic) interactions (9).

Provision of DTC genetic testing

In Slovenia, there are currently 5 commercial companies offering DTC genetic testing (9–13). None of Slovenian DTC companies is listed as part of Slovenian healthcare system and no DTC services are covered by National Health Insurance Company. Their laboratories are not a part of nationally regulated system and do not comply to the document on Rules on the conditions that must be met by laboratories to carry out investigations in the field of laboratory medicine, issued by Ministry of Health (7). According to web pages of DTC GT providers, some of the laboratories are outside of Slovenia and for some, there are no publicly available details at all (9–13). There is no pre-test counselling involved. Post-test counselling, performed by “specialized experts in the field of medicine and pharmacy“ (cited from webpage of private companies) is or is not included, depending on the test and company. None of the DTC GT providers offer genetic counselling by the experts trained and licensed for clinical genetics in Slovenia according to the data available on their web pages and Medical chamber of Slovenia (14). DNA analysis comes in form of personalized report with action plan for healthy nutrition and prevention (also for babies). Some companies advertise partnership with several private medical practices.

In addition, in Slovenia, there are currently 3 Health Insurance Companies offering DTC GT as an added value when buying a health insurance policy. Providers declare confidentiality of genetic data that cannot be accessed by Health Insurance Company for any other purpose. Tests are offered in collaboration with one of the 5 DTC GT companies.

Advertising of DTC genetic testing

DTC GT is often advertised as testing of a well-known correlation between defects in certain genes and diseases and clear guidelines for preventive actions given by a doctor specialist (10). A statement from DTC companies declares that a comprehensive genetic analysis will determine individual’s susceptibility to common diseases and provide preventive measures (12). They also state that their primary mission is to use the scientific discoveries in the field of genetics for creating a better and healthier life for individuals and their families (10). Majority of these statements are misleading and untrue and are advertised in order to promote test uptake and generate profit. Misleading statements create unreal consumer’s expectations and generate false certainty about test results.

Discussion

There are five private providers of DTC GT in Slovenia, the legislation on the subject is still under development and the public awareness of utility and significance of DTC testing is probably low. Although there is no specific law on DTC GT in Slovenia, our country has signed and ratified an Additional protocol to the convention on human rights and biomedicine in 2008, concerning Genetic testing for health purposes, adopted by Council of Europe (15,16). Also, Council of Experts for Medical Genetics has issued “An opinion about Genetic Testing and Commercialization of Genetic Tests in Slovenia” (6).

Main drawbacks related to DTC GT are the lack of medical supervision, scientific accuracy, clinical validity and utility of DTC genetic testing results and their interpretation (statistical risk assessment of genetic risk in multifactorial diseases where complex interactions of different genetic and environmental risk factors are involved) as well as inappropriate genetic testing of minors. Control of both pre and postanalytical requirements is poor and outside national or international regulations. In addition, DTC genetic test providers declare confidentiality of genetic data but possibility of discrimination if privacy is not maintained is still an important issue (17,18). Described situation in Slovenia is comparable to the current issues in other European countries (1,19,20). In addition, none of DTC GT providers laboratory is a part of nationally regulated system. Moreover, majority of the tests are performed outside of Slovenia, which makes it very hard or impossible to control.

There is no general agreement on scientific validity of the tests, their health and ethical implications and their legal status, although scientific community agrees with the fact that there is very limited or no clinical utility and validity of most of DTC tests (2,19–24). Even more critical is the fact, that proper genetic counselling is not part of any DTC GT in Slovenia, although genetic counselling is a crucial part of the process of any genetic testing, recommended by Council of Europe and all professional societies worldwide (25,26). Some European countries already have a law on genetic testing and all of them stated that genetic testing is only applicable for medical purposes and should be supported by genetic counselling and clinical genetic services. This is also supported by most of European clinical geneticists - generally, they are against the currently widespread way of offering DTC GT for specific severe or late onset diseases (2).

Another important issue is DTC testing performed in children. Commercial companies offer testing for adult onset diseases also in children, which raises number of ethical, legal and social issues (19). The European Society of Human Genetics (ESHG) recommends genetic testing on a person who does not have the capacity to consent only if it is for his or hers direct benefit. Therefore, for predictive genetic testing to be performed in minors, a considerable risk for inheriting a disease must exist and therapeutic or preventive measures must be available.

Last but not least, results of DTC GT do not consider individuals family history. Analyzing only certain genetic variants and not considering family history impact on absolute risk may result in false sense of security. At the same time, the results may raise unjustified worries and create stress by disclaiming inaccurate risks.

The European Society of Human Genetics (ESHG) opposed premature DTC commercialization of various genetic tests, stating “predictive value must be sufficient to meet the standards for clinical use. Clinical utility of a genetic test should be an essential criterion for deciding to offer this test to a person” (20). None of current DTC genetic test offers in Slovenia meets these criteria. It is widely believed that, unfortunately, currently offered DTC GT is only a messenger of forecoming wide availability of whole genome sequencing of individuals (17). Prices for individual’s exome or genome sequencing are dropping and their clinical validity and utility is increasing. With extensive genomic profiling being more available important issues will be raised. The ways to regulate ethical, legal, social in addition to clinical issues need to be discussed and set down, also with respect to the field of DTC GT.

In conclusion, there are five private companies offering DTC GT in Slovenia. Despite the fact that Slovenia has signed the Additional protocol to the convention on human rights and biomedicine, concerning genetic testing for health purposes, there is lack of or no medical supervision, clinical validity and utility of DTC GT results and their interpretation. Moreover, inappropriate genetic testing of minors is available. There is urgent need for regulation of ethical, legal, and social aspects, in addition to clinical issues and National legislation concerning DTC GT is currently being developed in Slovenia.